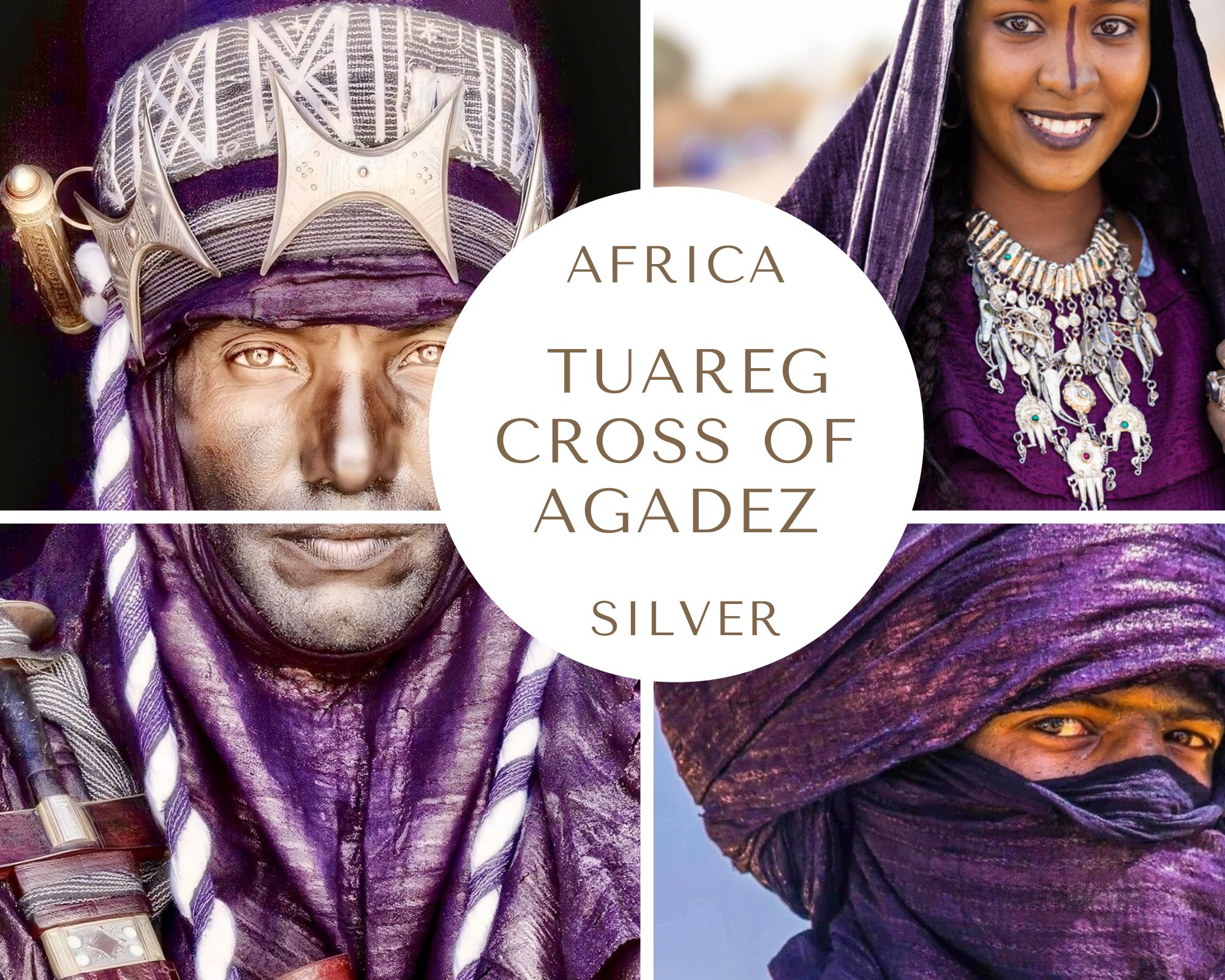

ZULU UKHAMBA AND ISICHUMO BASKETS

South Africa on the globe

(Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Kwa Zulu-Natal Province (source: Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Scatterlings Of Africa – Johnny Clegg & Juluka

Johnny Clegg (1953-2019) was a South African musician, singer-songwriter, dancer, anti-apartheid activist, and anthropologist. He was a professor of Zulu music and dance at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Nicknamed “The White Zulu,” Clegg composed the 1982 studio album Scatterlings, which mixed Zulu music with Afro-pop and Western rock. The song Scatterlings of Africa, heavily influenced by Zulu ngoma dance and music, was a worldwide hit, but it also put Clegg and his multiracial band, Juluka, under the police’s spotlight. At that time, South Africa was under apartheid, a system of strict laws that enforced racial segregation in every aspect of society, including music and performance spaces. The government officially and unofficially discouraged or prevented multiracial bands from performing publicly, viewing their presence as a challenge to the racist status quo. Clegg and Juluka frequently had trouble with the police, and state-run radio stations banned their songs.

In the early morning haze of a KwaZulu-Natal homestead, a grandmother sits cross-legged on a reed mat. Her fingers rhythmically dance through coils of ilala palm. Around her, children chase chickens, wood smoke fills the air, and laughter rises like birdsong. Her hands do not rush—they remember. Each twist and fold brings the ukhamba into being—not merely as a basket, but as a three-dimensional story.

“Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,” she says softly—a person is a person through other people. In Zulu culture, everything is communal, inherited, and shared. Few traditions embody this better than the craft of basket weaving. The ukhamba, used to carry sorghum beer during weddings and ancestral rituals, and the isichumo, which once cradled fresh milk in the cool shade of a hut, are more than tools. They are touchstones of identity—artifacts that connect the maker to the land, family, and ancestors.

Crafted from sun-dried grasses and earth-toned dyes, these baskets are beautiful and intimate. Their tightly woven forms echo the shape and purpose of clay pots, but they are softer and more forgiving, much like the hands that make them. Their patterns are often geometric, symbolic, and specific to family lineages. These patterns are passed down through generations of women who teach without words.

During ceremonies, these baskets are passed from hand to hand and are filled with gifts, drinks, or stories. Their presence transforms everyday moments into something sacred. Even in a modern world dominated by plastic and glass, ukhamba and isichumo baskets endure as emblems of resilience, memory, and pride.

Through these vessels, the Zulu people express who they are, where they have been, and the quiet brilliance of a heritage that endures not only in grand monuments but also in the humble, reverent act of creation.

Zulu women making ilala baskets, KwaZulu Natal, 2009. Photo by Veronica Thompson / Alamy.

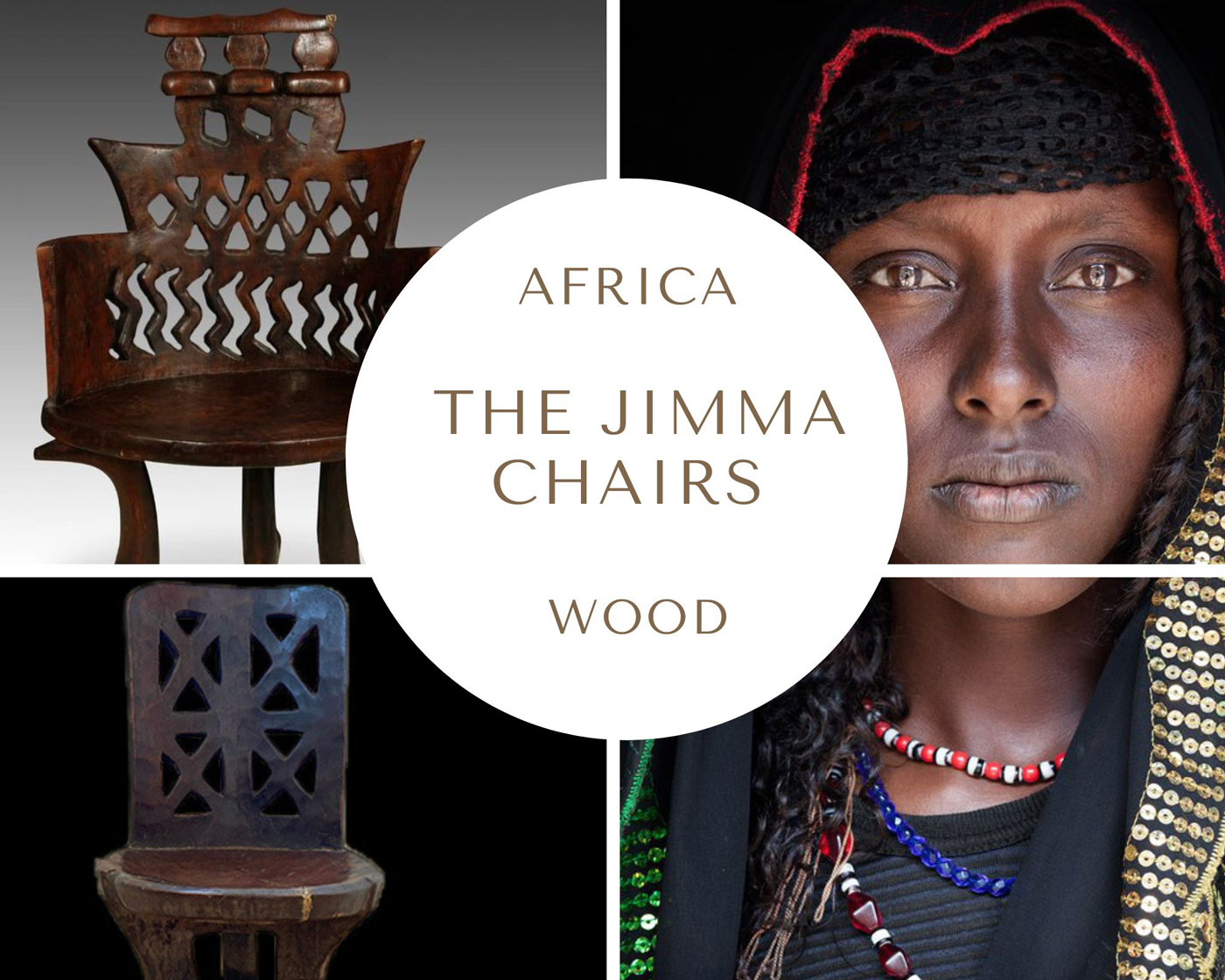

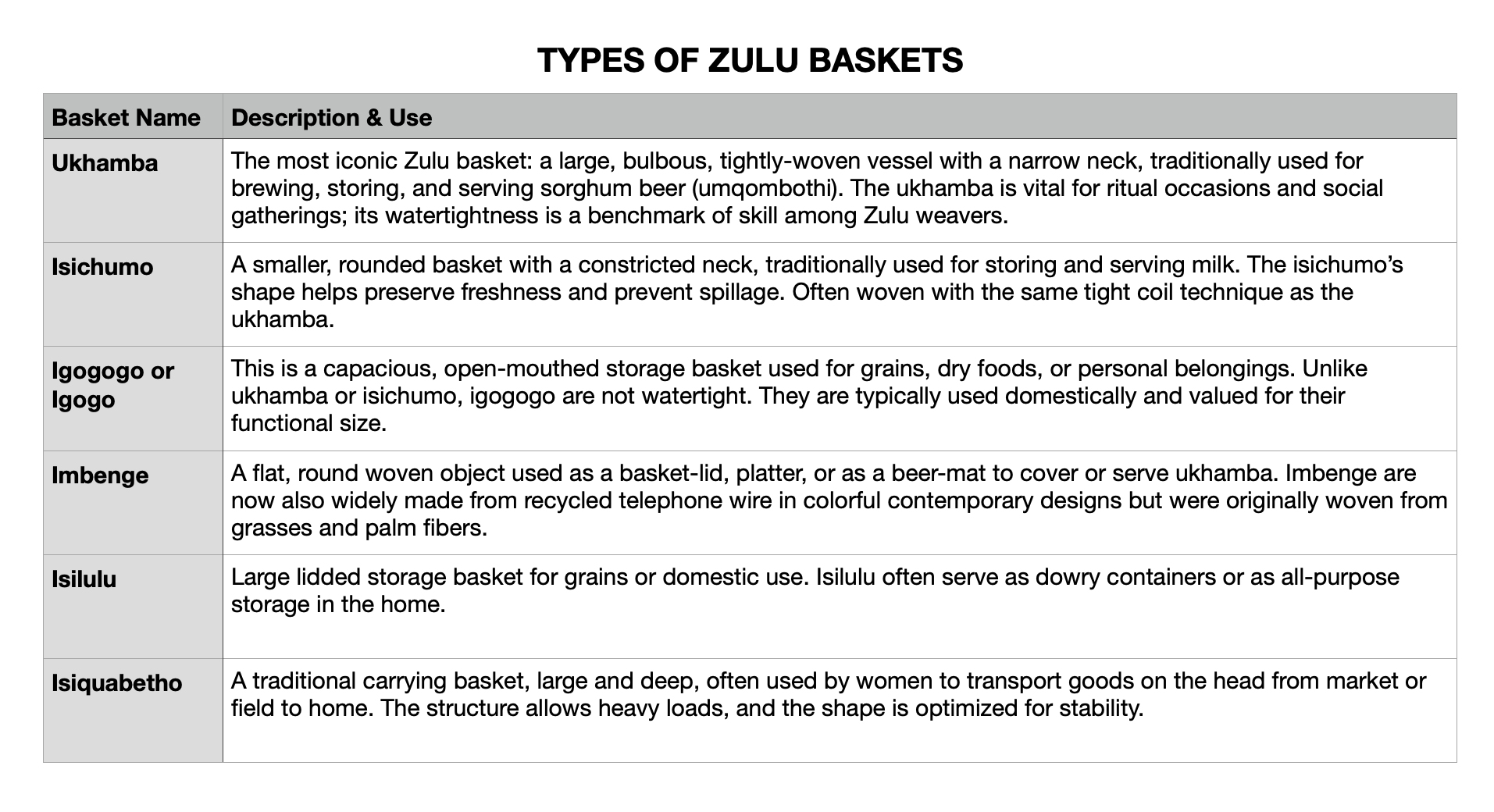

A Universe of Baskets: The Living Forms of Zulu Weaving

The Zulu people have developed a rich basket-making tradition, with each form intricately tied to specific functions, rituals, and social meanings. The following Zulu basket types are most frequently described in academic studies and museum catalogues, though regional variations and contemporary innovation mean there may be minor or local forms beyond the core list.

Lesser-Known or Occasional Baskets

- Igqokwane: A small, lidded basket typically used for storing snuff, personal belongings, or medicine.

- Umgqomo or Igomo or Iqoma: A large, open basket used for storing or winnowing grain. It is not watertight or suitable for liquids.

- Izinkezo (not a basket type but a basketry spoon): Sometimes listed as a companion object, traditional spoons are occasionally woven from the same materials as baskets and are used for serving beer or food.

- Ukwakha: A rare, functional work basket that is sometimes referred to in ethnographic literature and is used for specific farming or gathering tasks.

- Iquthu: The smallest Zulu basket. Called the “herb basket,” the iquthu is usually made by elders and beginners and comes in different colors and patterns. “The iquthu is a small container with thin walls, usually 4 to 8 inches tall, which uses the wicker-work twined technique” (Rhoda Levinson, Basketry: A Renaissance in Southern Africa).

Notes on Nomenclature

- Variant spellings and names can occur due to regional language differences or changing usage over time.

- Some modern or export-oriented baskets, especially those made for sale rather than for domestic use, deviate from traditional shapes and may not have Zulu names.

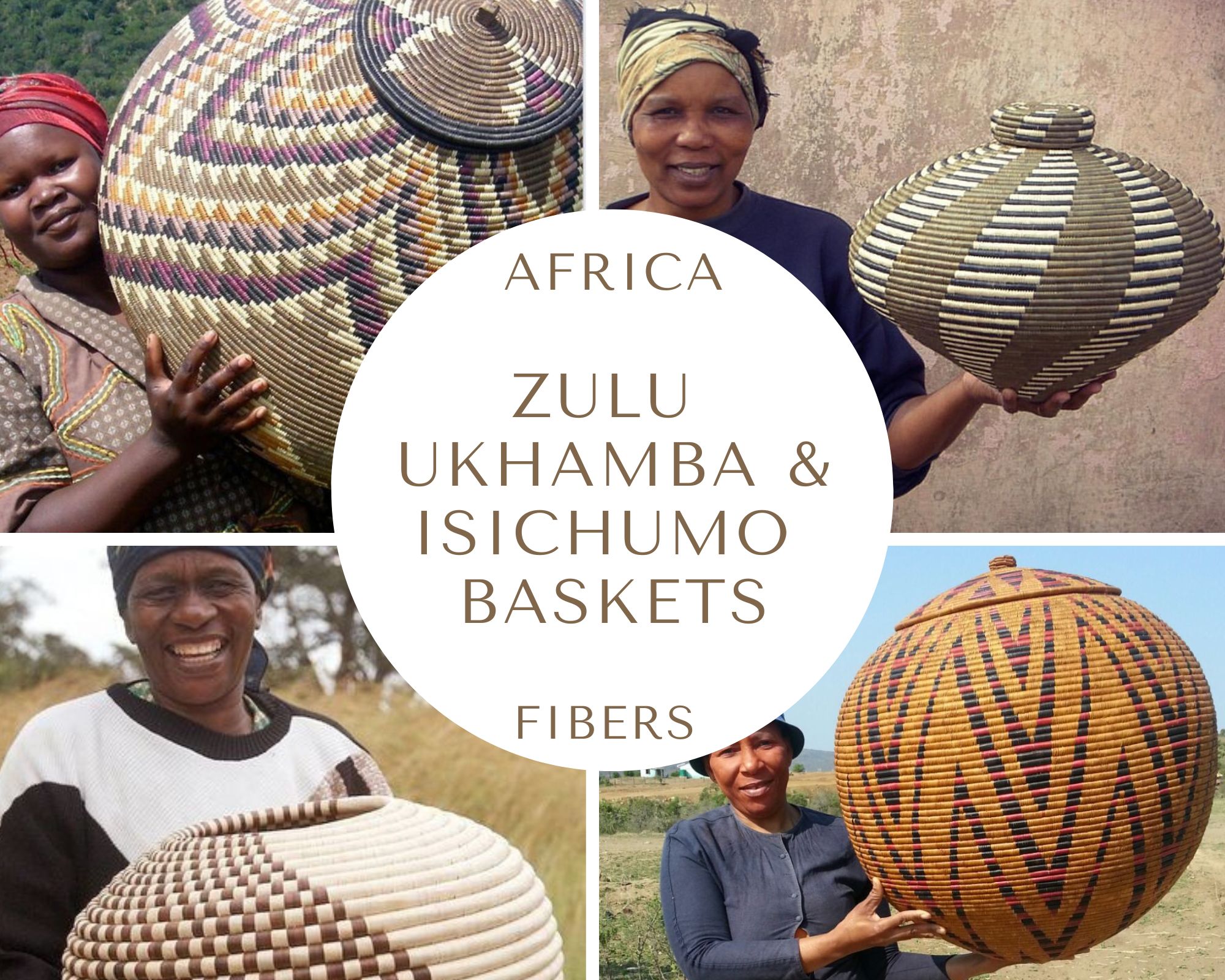

Three modern Isichumo baskets, made from coiled and woven grasses. Diameters: 13 in., 33 cm; 15 in., 38 cm; 16 in., 40.64 cm. Kombi Design Showroom, New York, USA.

These isichumo baskets have been made “by Beauty Ngxongo, one of southern Africa’s preeminent contemporary weavers who has blurred the line between utilitarian craft and fine art. The colors are obtained from natural sources – black fibers are produced by boiling the ilala palms with the indigo plant, while reddened sorghum leaves produce fibers with a reddish brown color. Nxgongo’s work is represented in all the major South African museums, including the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town”. (Kombi).

The isichumo was originally a large, pear-shaped basket made using the coiling technique. It was tightly woven because it had to contain liquid. It was frequently used to carry beer on one’s head.

Old Zulu isiquabetho coiled basket from the 20th century in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It is likely woven from ilala palm and features the “Man in the Maze” weaving pattern of the Akimel O’odham peoples in varying gradients of brown fronds. Dimensions: height 6.25″ (15.9 cm), diameter 16.75″ (42.54 cm). It was auctioned in 2023 by John Moran Auctioneers in Monrovia, California, USA.

Vintage Zulu Isiquabetho Open Basket from the 20th century, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. This beautiful Isiquabetho basket was used to store grain and for serving. Dimensions: height 7″ – 17.78 cm, diameter 25″ – 63.5 cm. Cultures International From Africa To Your Home, CA, USA.

This is a group of five Zulu Isiquabetho coiled baskets, made in the 2000s in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. They are likely woven from ilala palm and comprise five African baskets, each woven with intricate geometric motifs in various gradations of brown. The artists include Mahurero Twapika, Maria Thenu, and Mberu Rugugu. Dimensions: The largest basket is 5″ tall and 16″ in diameter, and the smallest is 5″ tall and 14.25″ in diameter. They were auctioned in 2023 by John Moran Auctioneers in Monrovia, California, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM

1. Old large Isilulu basket. Dimensions: circumference 50 in., 127 cm; height 9.5 in., 24.13 cm. WorthPoint.

2. Old large Isilulu basket. Dimensions: diameter 10 in., 25.4 cm; height 10 in., 25.4 cm. WorthPoint.

3. Old large Isilulu basket from the early 20th century. Dimensions: circumference 45 in., 114.3 cm; height 13 in., 33 cm. WorthPoint.

4. Old large Isilulu basket from the early 20th century. Dimensions: circumference 33 in., 83.82 cm; height 7 in., 17.78 cm. WorthPoint.

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

1. Imbenge beer pot lid from ca. 1950. Diameter: 7.87 in., 20 cm. Galerie Bruno Mignot, African Primitive Art Gallery, La Wantzenau, France.

2. A Zulu beer pot with incised wave decoration and imbenge cover. Total height: 11.4 in., 29 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Stephan Welz and Co., Johannesburg, Cape Town, Pretoria, South Africa.

3. Ukhamba beer pot with Imbenge lid. Diameter: 7 in., 18 cm. African Traditional Home and Wear, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

4. Vintage Imbenge Beer Pot Cover, South Africa, from the 1960s. Diameter: 7.48 in., 19 cm. Pan After, Collingwood Vic. Australia.

5. Imbenge from the first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 1 3/4′ in., 4.5 cm, diameter 7 1/2 in., 19 cm. Spencer Museum of Art, Kansas, USA.

The imbenge is both useful and beautiful. It serves as a vessel for dried foods and a cover for clay beer pots when upturned. When its work is done, it rests on the wall. It is not forgotten, but displayed. Its woven patterns add quiet grace to the home.

Now, let’s turn our attention to beer and the beloved beer pot. Sadly, we can’t share a sip together!

The Zulu sorghum beer: utshwala, umqombothi

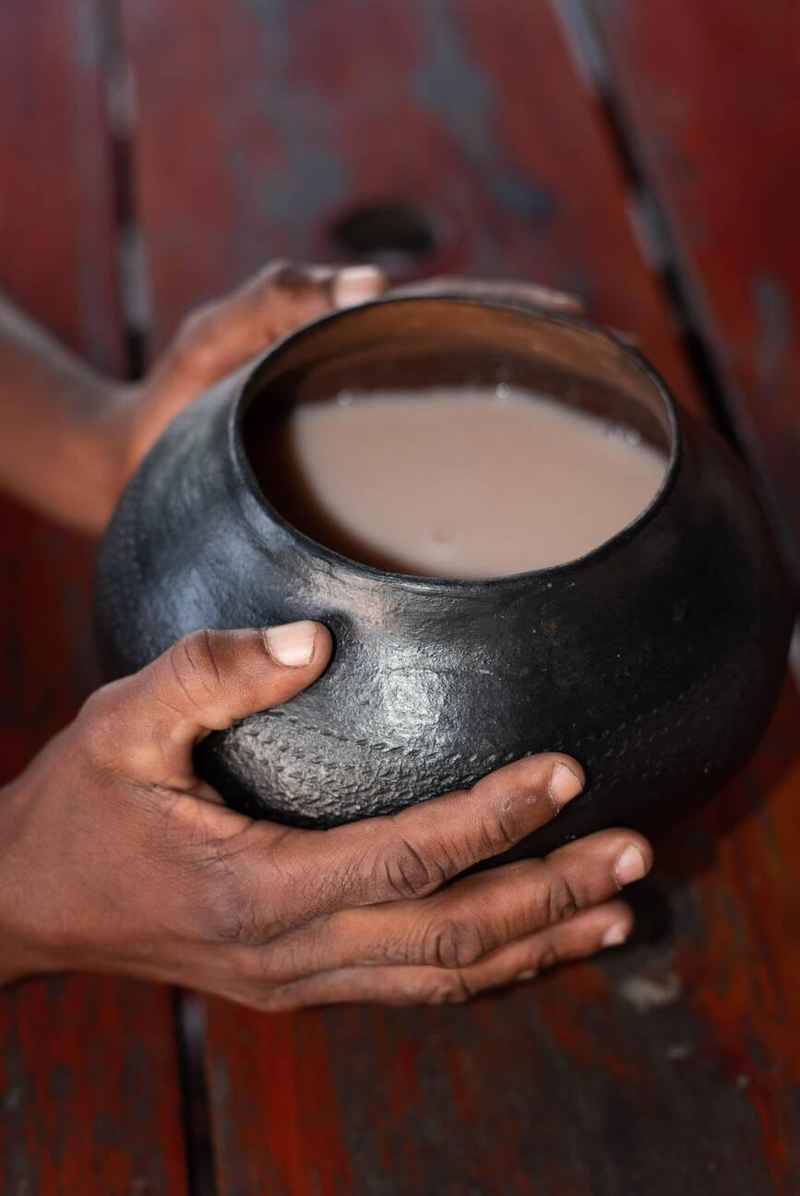

At the heart of many Zulu social and ritual gatherings is sorghum beer. Brewed from sorghum grain and water — sometimes with added maize — this traditional beer is thick and rich in nutrients, typically low in alcohol content. It is not only a beverage but also a vital element in ceremonies that honor ancestors, mark milestones such as weddings and funerals, and foster community bonds. In Zulu society, preparing and sharing beer is considered an expression of hospitality, respect, and togetherness.

The traditional Zulu sorghum beer is called utshwala. Umqombothi is a more common term in South Africa, especially among Xhosa speakers, but utshwala is the primary term used by the Zulu people for their traditional beer. This beer has been made in the Zulu region for at least a millennium, and it remains relevant today. Its communal drinking emphasizes the interconnectedness of humanity.

Utshwala is also believed to be the food of the ancestors, who enjoy its smell. The black color of the beer pots, which are fired twice and rubbed with wax or animal fat to create a burnished appearance, is also intended to please the ancestors, who are drawn to darkness and quiet. The imbenge lid is not fitted tightly to the ukhamba pottery so that a small gap remains through which the spirits of the ancestors can slip in to take their share of the drink.

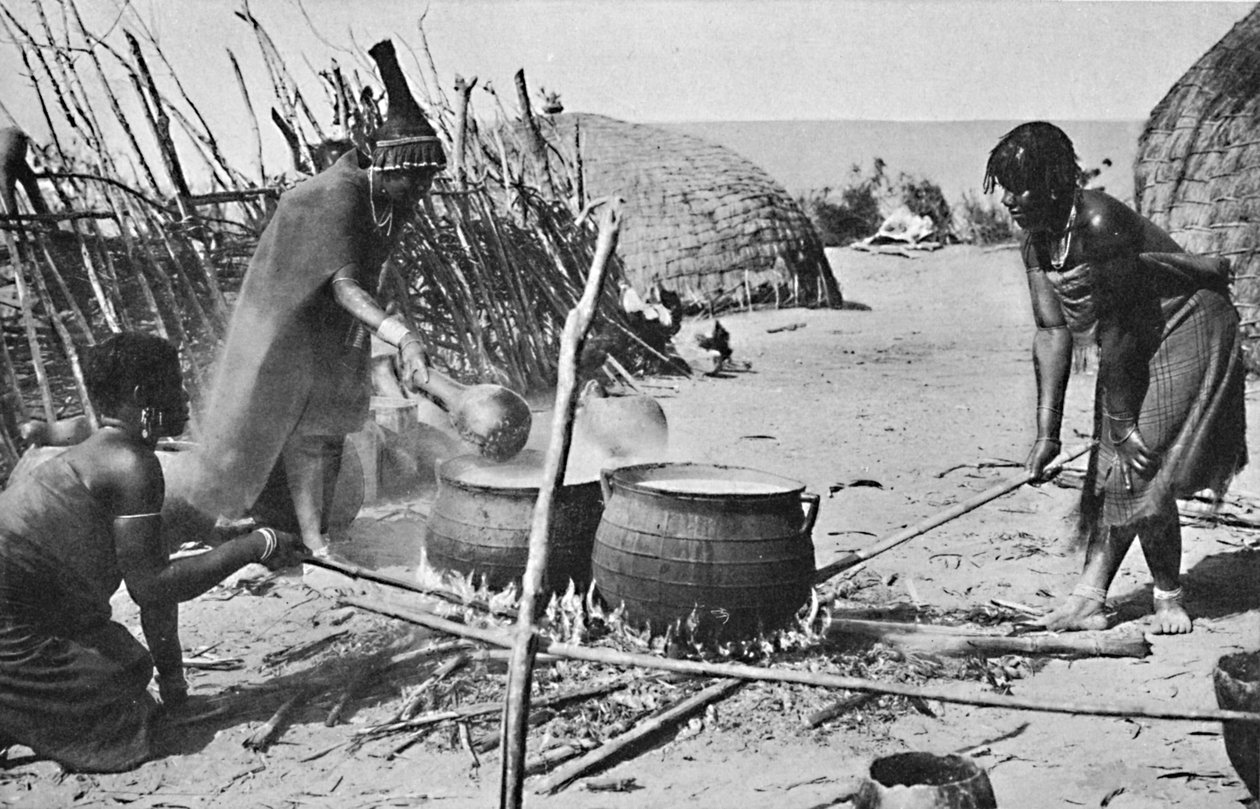

Zulu wives brewing utshwala beer, Natal, 1912.

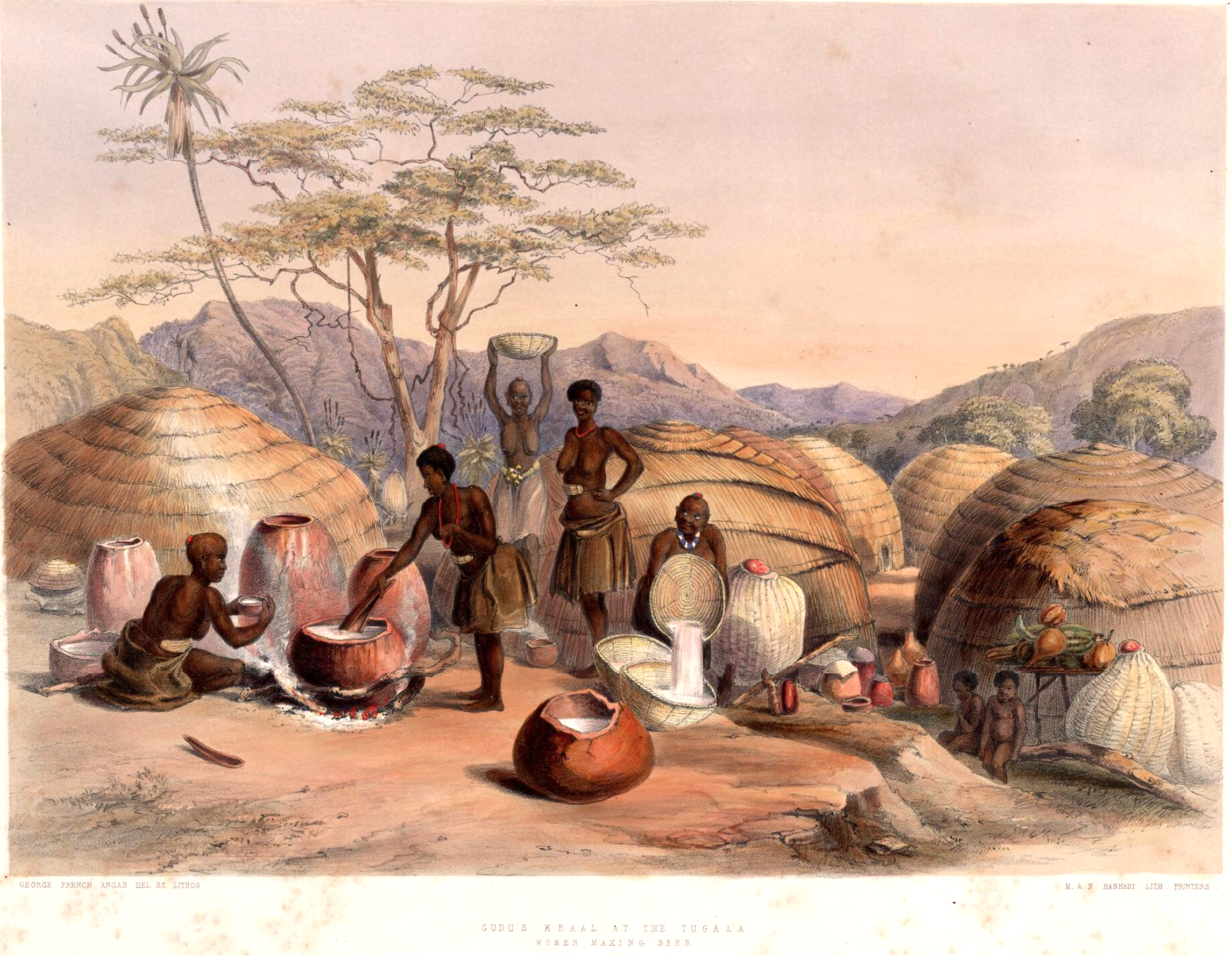

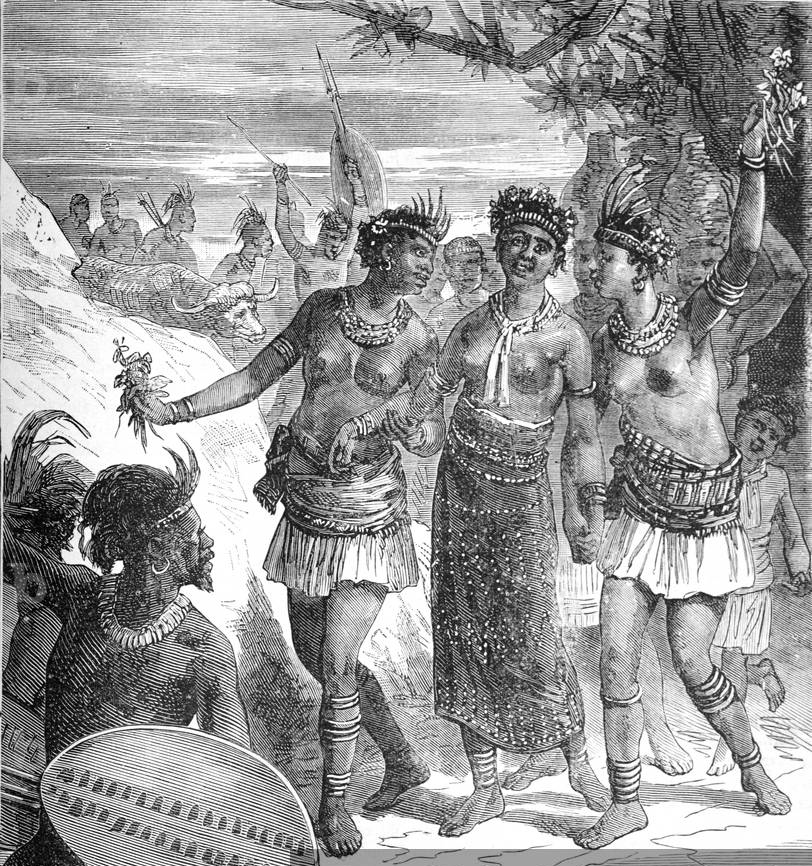

Gudu’s Kraal at the Tugala, Zulu women making beer is a hand-colored lithograph by English traveler and illustrator George French Angas depicting Zulu women making beer. Digital Archive of the National Library of Australia.

This lithograph and others by Angas, as well as some wood engravings copied from his works, were originally printed in The Kafirs Illustrated, which was published in London in 1849. Angas copied the lithographs from his original watercolor paintings, which portrayed the people, landscapes, and wildlife he observed in South Africa. Like other Victorian artists of his time, Angas primarily worked for European audiences, creating picturesque and romantic ethnographic portrayals full of easily accessible exoticism to satisfy the increasing curiosity and demand. However, these drawings accurately depict the natural history and people of South Africa. Consequently, they are considered a valuable visual resource for understanding Zulu material culture in the first half of the 19th century. Note the simultaneous use of earthenware and ilala palm beer containers.

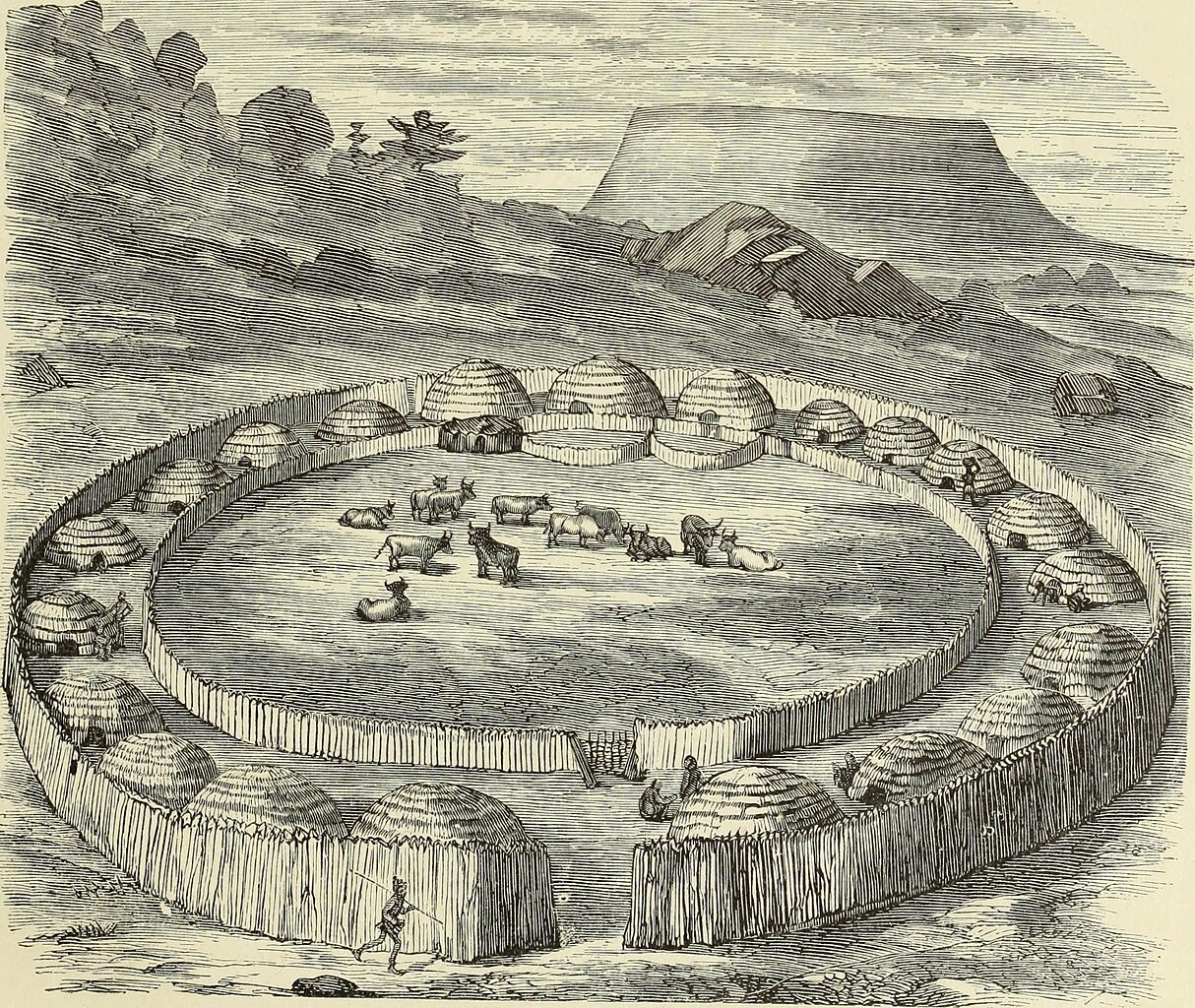

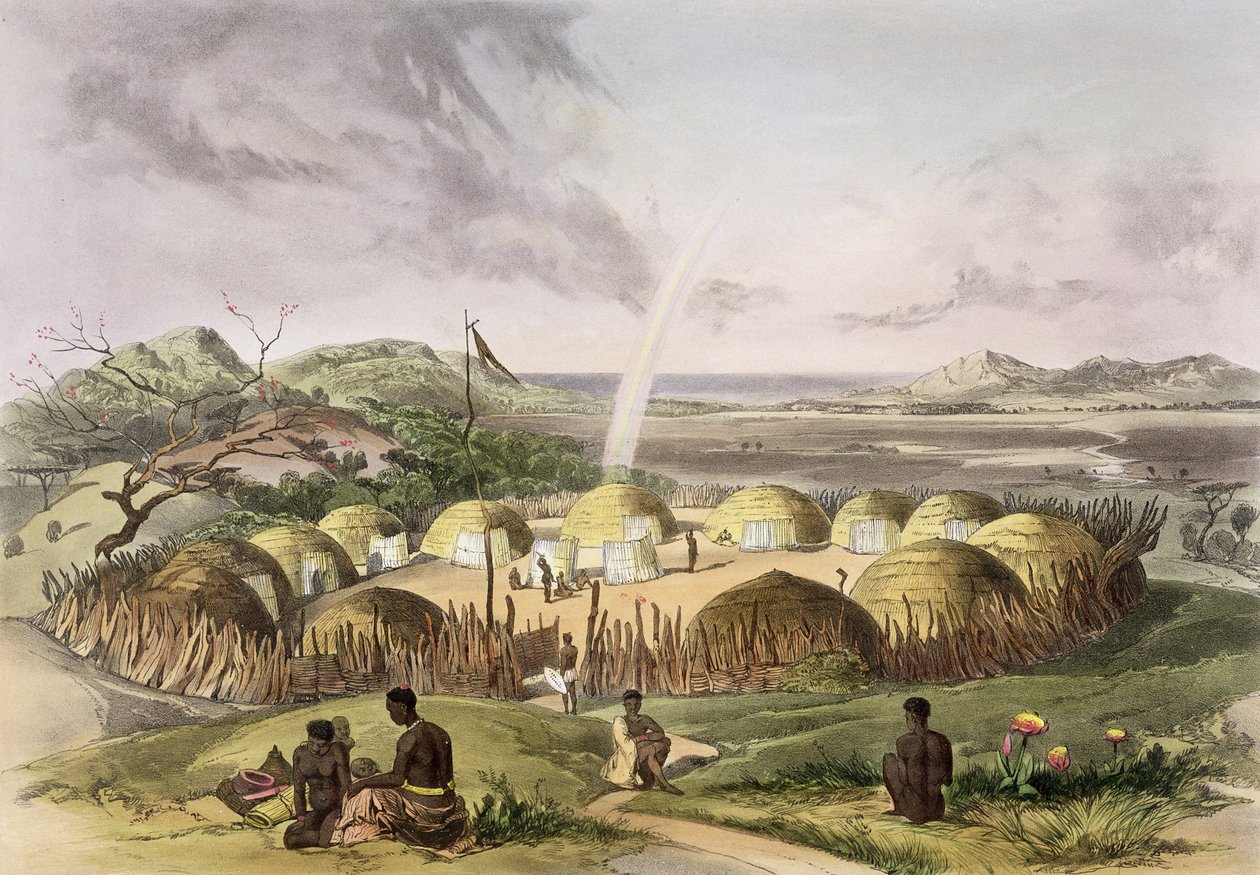

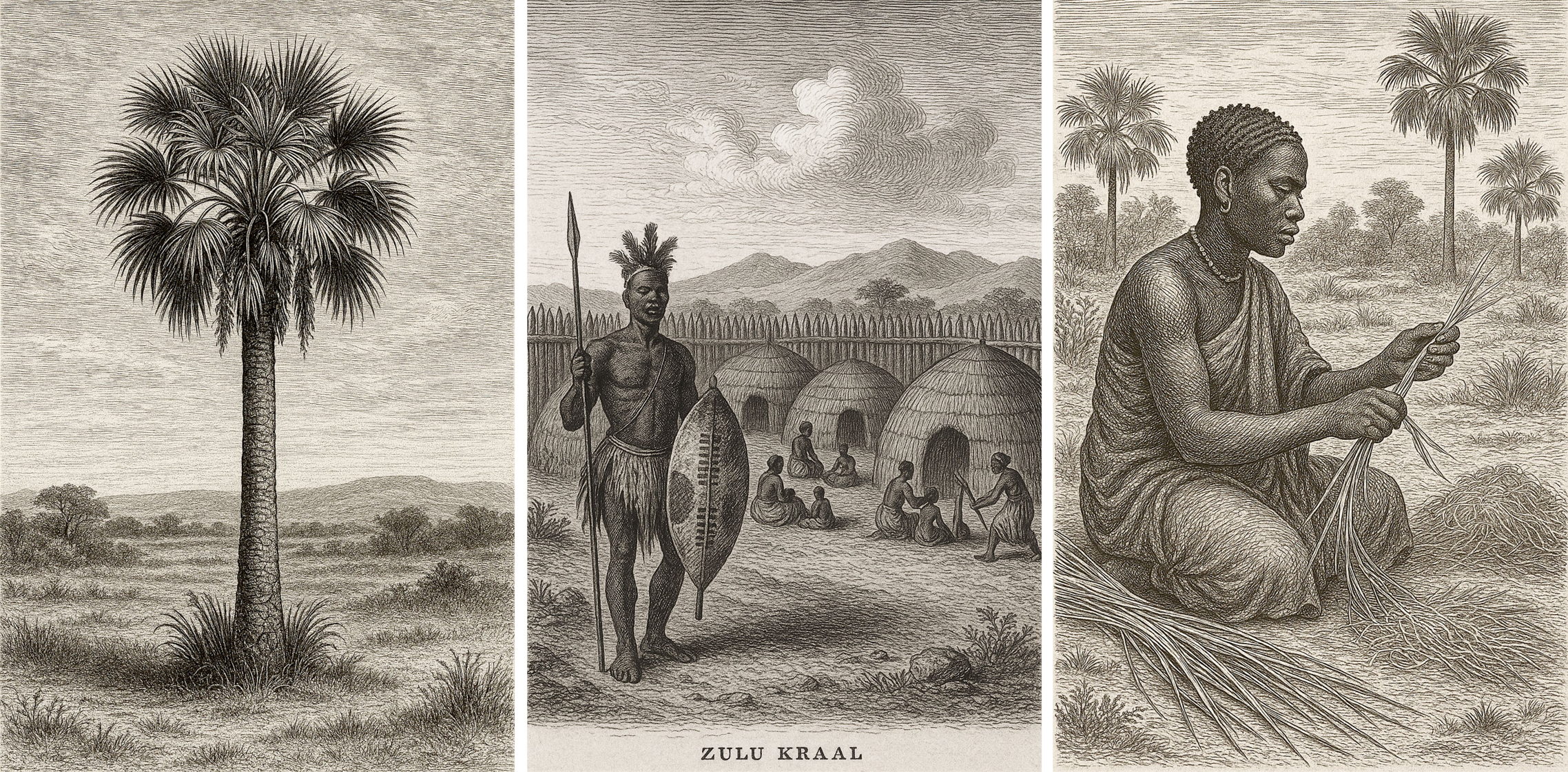

A Zulu kraal is a traditional homestead and livestock enclosure typical of the Zulu people of South Africa. Constructed using locally available materials, it was a large, circular enclosure consisting of upright wooden posts, interwoven sticks, and thatch. A typical kraal consisted of a central cattle enclosure (isibaya) surrounded by a ring of beehive-shaped huts (iQukwane) for family members. The chief’s hut was positioned prominently. This layout reflected the Zulu social organization, emphasizing spatial hierarchy and the clear separation of family units. The design emphasized security for livestock and the symbolic organization of space within Zulu society, as confirmed by anthropological and architectural research.

Zulu Kraal enclosing 21 Huts, engraving printed in the volume The uncivilized <sic!> races of men in all countries of the world; being a comprehensive account of their manners and customs, and of their physical, social, mental, moral and religious characteristics, by Rev. John George Wood, 1870-71, J. B. Burr & Company, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Zulu Kraal Near Umlazi, Natal, Plate 27 by English traveler and illustrator George French Angas, from ‘The Kafirs Illustrated’, 1849. Digital Archive of the National Library of Australia.

Yvonne Chaka Chaka – Umqombothi, Afro-pop song released in 1988.

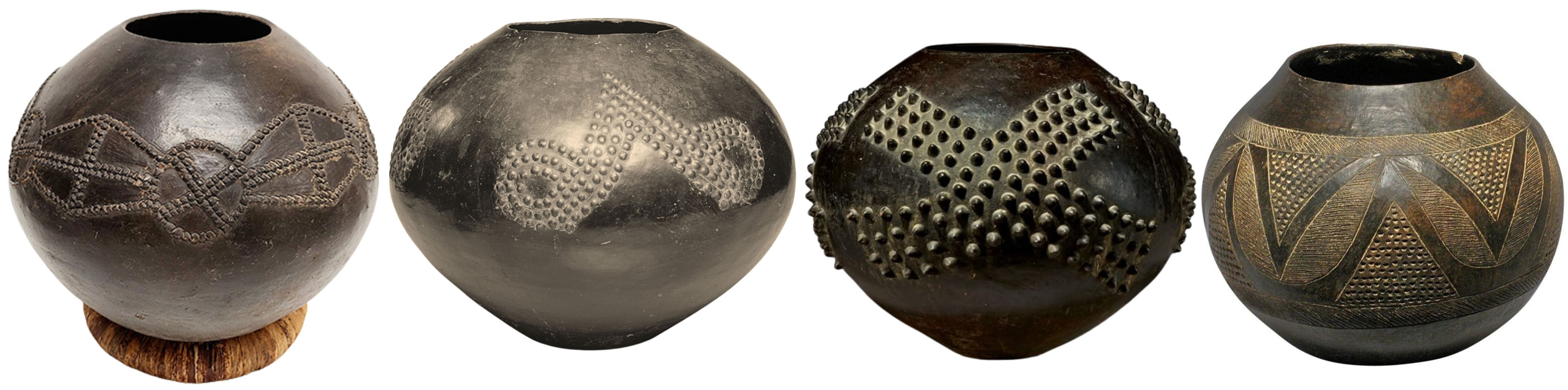

The Clay pot: ukhamba

This classic clay pot is traditionally used for fermenting, storing, and serving sorghum beer. It is widely used as a communal drinking vessel. These pots are expertly hand-built with a wide body, slightly narrowed neck, and rounded base—the perfect form for fermentation and communal drinking. Zulu potters often polish the surface and occasionally decorate it with subtle incisions or burnishing. However, they generally avoid over-embellishment because the form itself is both functional and symbolically significant. The clay’s porous nature helps regulate fermentation, enhancing the beer’s distinctive character. In Zulu homes, especially during important rituals, the ukhamba symbolizes abundance, hospitality, and reverence for tradition.

The ukhamba is usually a thin, rimless vessel with a rich black color. Coil-built, it is burnished and decorated with raised bumps known as amasumpa. These bumps are a hallmark of Zulu pottery and are thought to represent cultural symbols such as cattle (a sign of wealth), an aerial view of a village, or traditional scarification marks.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Zulu Ukhamba. Medium: Earthenware. Timothy S. Y. Lam Museum of Anthropology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

2. Zulu Ukhamba from the early 20th century. Medium: Earthenware. Dimensions: 10 1/2 x 13 3/4 x 13 3/4in.; 26.7 x 34.9 x 34.9 cm. Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

3. Zulu Ukhamba. Medium: Earthenware. Height: 12 in., 30.5 cm. Pinterest.

4. Zulu Ukhamba from the mid-20th century. Medium: Earthenware. 1st DIBS.

Zulu women bringing beer to a wedding ceremony. Date: November 1937. Wellcome Collection, Wellcome Trust Corporate Archive, London. UK.

South Africa postage, 2013. Symbols of South African Cultures Issue, Ukhamba.

The transition to the fiber ukhamba

From the 19th to the 20th century, Zulu artisans in regions where the ilala palm (Hyphaene coriacea) grows began weaving ukhamba vessels from its fibers. Using refined coiling techniques, they produced remarkably watertight baskets. The ukhamba’s woven design replicates the elegant, bulbous profile of its ceramic ancestor but introduces new possibilities for vibrant patterning with dyed natural fibers. This transition did not eliminate the ceramic tradition but rather complemented it, reflecting the adaptability and creativity of Zulu craftswomen.

The shift to fiber also has social dimensions: Basket weaving provides economic opportunities for women, especially in the contemporary era. Both ritual and commercial baskets are highly prized in South Africa and beyond. In both clay and palm, the ukhamba remains an emblem of Zulu identity—a vessel that holds not just beer, but also the spirit of community, memory, and artistic legacy. Beyond its functionality, the ukhamba embodies deep social, ritual, and aesthetic significance within Zulu society.

Old traditional Zulu ukhamba ceremony basket. Diameter: 14 in., 35.56 cm. Auctioned in 2025 by Holabird Western Americana Collections, Reno, NV, USA.

A group of five modern izinkamba. The biggest is 16 x 12 in., 40.64 x 30.48 cm. Auctioned in 2021 by Leland Little, Hillsborough, NC, USA.

Three izinkamba from the second half of the 20th century. Pinterest.

Ukhamba, vessel of stories

As we saw, the term ukhamba designates both an earthenware pot and a particular kind of basket. The Zulu ukhamba basket, renowned today for its fine, coiled ilala palm construction, evolved artistically and practically from its earlier clay counterpart. While the original ukhamba pots were made of clay, coiled palm-fiber baskets spread throughout the Zulu heartland, especially in northern KwaZulu-Natal, over the 19th and 20th centuries. This region is uniquely rich in ilala palms. This ecological abundance enabled the substitution of materials and the parallel coexistence of clay and fiber vessels, each of which was adapted for use in communal beer rituals and daily storage.

Terminology and Etymology

The term ukhamba (plural: izinkamba) is deeply rooted in the Zulu language and philosophy. It offers insight into the vessel’s perceived role and significance. It is believed to be a combination of two Zulu words: ukukhama, meaning “to squeeze out and compress,” and bamba, meaning “to contain or receive.” This etymology suggests a powerful metaphor for the human mind, which is capable of extensive thought and memory and has the capacity to hold and process a wealth of information and experience. Thus, the ukhamba is not merely a container for beer, but a reservoir of knowledge and tradition that nourishes both the physical and spiritual worlds. This philosophical underpinning elevates the vessel’s status, framing it as an object that embodies knowledge, tradition, and the collective memory of the community.

The terminology associated with the ukhamba and related vessels is specific and reflects their varied functions within Zulu culture. For example, large pots used for brewing beer are called imbiza (plural: izimbiza), and smaller pots used for serving are called umancishana. The lids for beer baskets or pots are called imbenge (plural izimbenge) and are often shallow, saucer-like, and woven. The beer itself, utshwala, is central, and its consumption is integral to Zulu hospitality and ritual.

The specific names of these objects and the beer they contain highlight the highly organized and codified nature of Zulu material culture.

Each item has a designated name and a specific role in the intricate tapestry of social and ceremonial life.

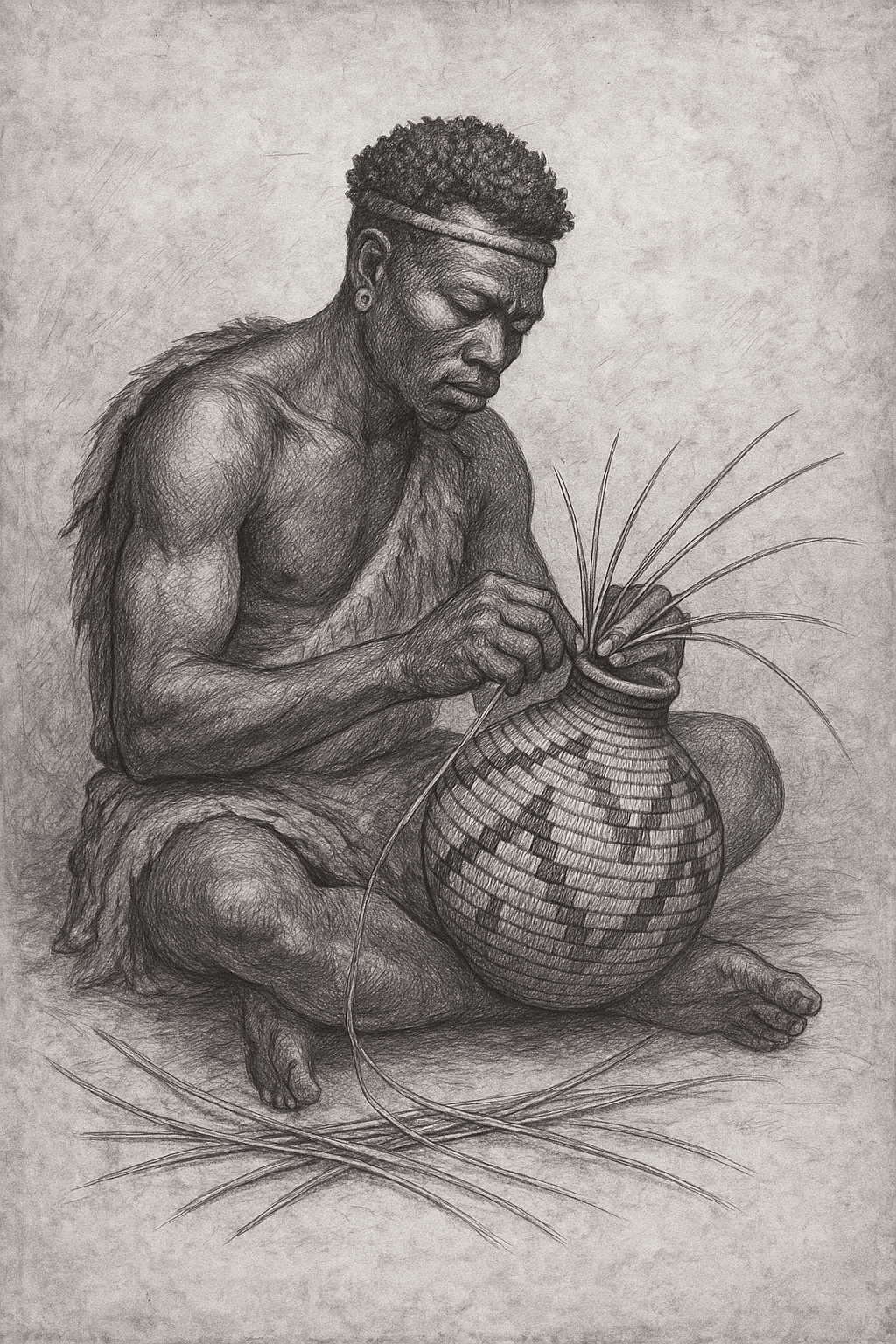

The Role of Men in Early Weaving

In pre-colonial and early colonial Zulu society, basket weaving was traditionally a male-dominated craft. They were responsible for creating various woven items, such as baskets and mats, which were essential for daily activities, including agricultural work and domestic storage.

This division of labor was a long-standing cultural norm, with specific skills and knowledge passed down from father to son. The creation of items like the ukhamba beer basket, central to social and ceremonial gatherings, was a significant male artisan responsibility. The quality and craftsmanship of these baskets reflected the weaver’s skill, and were a source of pride for the family and community.

However, the shift in this traditional gender role was a direct consequence of colonial intervention and the disruption of Zulu societal structures.

The Colonial Impact and the Shift to Female Weavers

The arrival of European colonists in South Africa in the 19th century profoundly impacted Zulu society. Traditional roles were disrupted, and the indigenous craft of basket weaving nearly collapsed. The colonial economy was driven by the demand for labor in the growing mining and agricultural sectors, which resulted in the large-scale conscription of Zulu men. This forced migration to work in the mines removed the primary artisans from their communities, breaking the traditional chain of knowledge transmission from father to son. As men abandoned their roles as weavers, production of essential items like baskets and mats plummeted, threatening the survival of the craft. This was not merely an economic disruption; it was a cultural and social upheaval that severed the connection between the artisans and their communities. This led to a period of decline and uncertainty for Zulu basketry.

The introduction of foreign goods through trade further exacerbated the decline of traditional crafts. As European utensils, such as cups, containers, and pans, became more widely available, the practical necessity for handcrafted items diminished. The convenience and novelty of these imported goods shifted consumer preferences, with many Zulu people opting for the new products over traditional, labor-intensive baskets. This change in demand, coupled with the absence of male weavers, pushed the art of basket weaving to the brink of extinction. The craft, which had been a cornerstone of Zulu material culture for centuries, was in danger of being lost forever—a casualty of the disruptive force of colonialism on indigenous societies and economies.

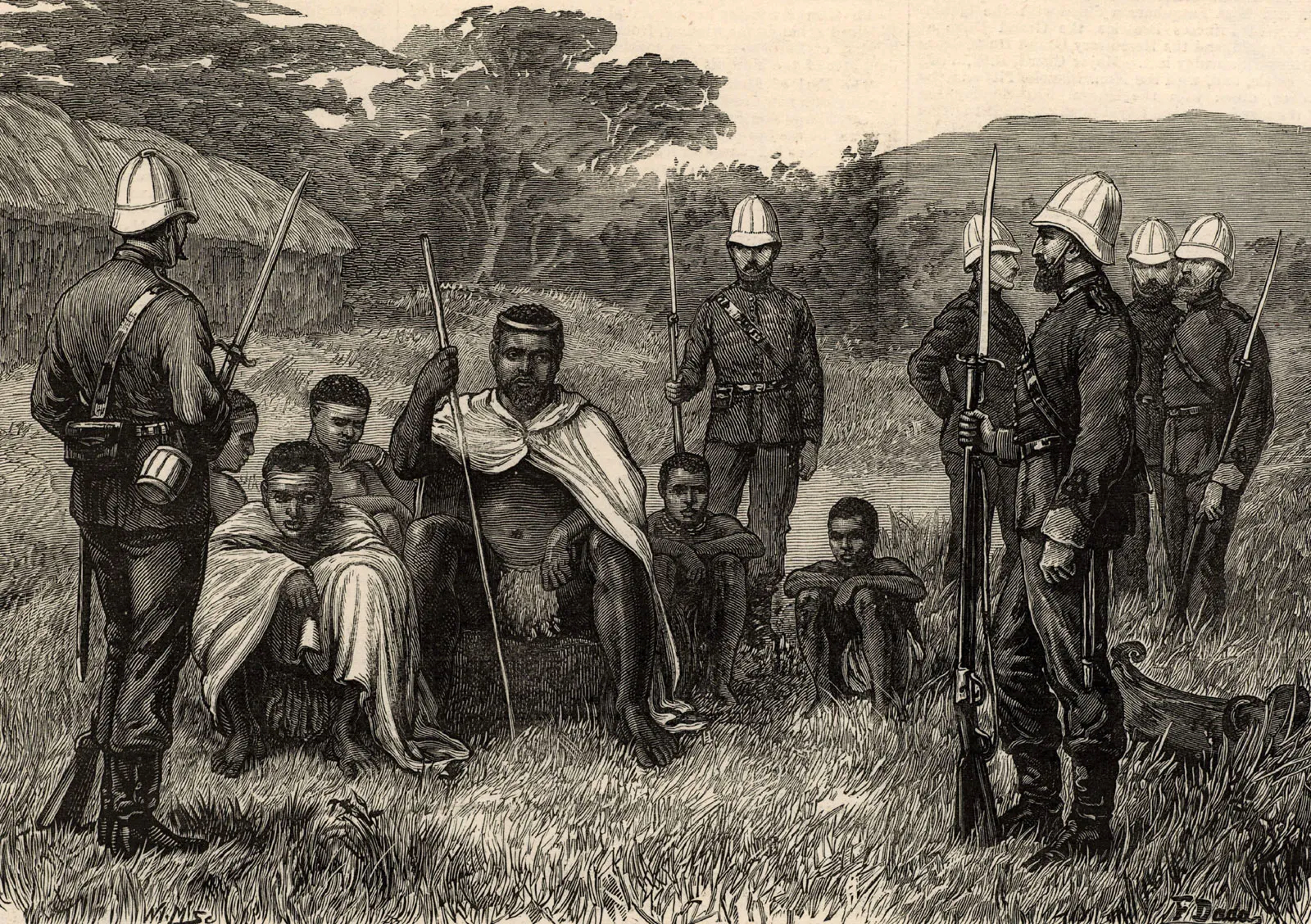

Cetshwayo, the Zulu king, is under British guard after the Anglo-Zulu War in southern Africa in 1879. Encyclopædia Britannica / Photos.com / Thinkstock.

The Emergence of Women as Primary Artisans

Following the disruption caused by colonialism, Zulu women became the new guardians of the basket weaving tradition. While the men were absent, working in the mines, the women filled the void by learning the intricate skills of weaving. They did so to provide for their families and preserve a vital part of their cultural heritage. This transition was neither immediate nor seamless, but rather a gradual process of adaptation and resilience. Women, who had previously been involved in other aspects of domestic and agricultural life, took on the responsibility of mastering a craft that had been exclusively male for generations. This shift was a testament to their ingenuity and determination to maintain their cultural identity in the face of immense external pressure.

The role of women as weavers was further solidified by European missionaries who established schools and workshops to teach Western crafts and skills in their efforts to convert the local population to Christianity. In line with European gender norms, these institutions often directed women toward activities such as weaving and sewing, thus reinforcing the new division of labor. For example, a Lutheran missionary is credited with establishing a basket-weaving school and recruiting older women to teach the craft, thereby playing a crucial role in its revival.

While this missionary influence was aimed at cultural assimilation, it inadvertently helped preserve the art of Zulu basketry by institutionalizing the role of women as its primary practitioners. Today, the remarkable women of KwaZulu-Natal continue the tradition, and their skill and artistry have transformed Zulu basketry into a globally recognized art form.

Contemporary Revival and Global Recognition

In recent decades, Zulu basketry—the ukhamba in particular—has experienced a remarkable revival and gained significant international recognition as a fine art form. This renaissance is due to the growing global appreciation for handcrafted, culturally authentic art and the efforts of master weavers and organizations to promote and market their work.

Although the role of weaving schools and workshops has evolved in contemporary times, their importance in preserving the craft remains undiminished. Organizations like Bambizulu are deeply committed to training and developing young artisans through their nonprofit arm, Edna’s Hope. They host workshops and weaving retreats where master weavers pass on their skills to the next generation, ensuring the continuity of the tradition. These modern schools teach traditional techniques and encourage innovation and artistic expression, allowing the craft to evolve while staying rooted in its cultural origins. By documenting techniques and stories, these institutions are creating a valuable archive of knowledge accessible to future generations. The ongoing work of these schools is a testament to the resilience of Zulu basketry and the dedication of the artisans determined to preserve their heritage.

Today, the intricate designs, vibrant colors, and exceptional craftsmanship of Zulu baskets have captured the attention of collectors, museums, and art enthusiasts worldwide. This provides a vital source of income for weavers, many of whom live in rural areas with limited economic opportunities. It has also instilled a sense of pride and cultural identity.

The work of master weavers like Beauty Ngxongo has been instrumental in elevating the status of Zulu basketry. Ngxongo is renowned nationally and internationally for her distinctive baskets, which feature vibrant designs and complex, masterful patterns. Her work and that of other leading artists is celebrated for blurring the line between utilitarian craft and fine art. Their elegant structural forms are enhanced by intricate graphic and chromatic designs. These contemporary masterpieces are featured in major museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the South African National Gallery, and are sought after by collectors worldwide. This global recognition has transformed the economic landscape for weavers and played a crucial role in the cultural revival of the Zulu people by preserving their heritage and sharing their artistry with a global audience.

Ethnobotanical Foundations and Plant Ecology

The ilala palm (Hyphaene natalensis or H. coriacea) is deeply embedded in the ecosystems of Tongaland and Zululand and became a pivotal resource for Zulu material culture. Regional surveys demonstrate the palm’s extensive distribution of over 10.5 million individuals across 156,000 hectares, providing a vast and sustainable source of material for basketry. The palms produced an annual yield of leaves that could be harvested for domestic crafts without endangering the resource. This access was crucial for establishing the ukhamba tradition in the region.

LEFT: Ilala palm, 2013, Kruger NP, South Africa; Wikimedia Commons.

TOP RIGHT: Ilala palm fibers. Africa Trading, Durban, Kwa Zulu Natal, South Africa.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Ilala Palm Fibers, Dathonga Designs. Weaving the Ilala fiber, Busani Bafana/IPS.

Harvesting and Preparation of Palm Fronds

The primary material used to make traditional Zulu ukhamba baskets is the frond of the ilala palm. Transforming these raw fronds into pliable weaving material is a meticulous, labor-intensive process traditionally undertaken by the women who ultimately weave the baskets.

The palm fronds are harvested sustainably; artisans select only mature leaves to ensure the continued health and regrowth of the palm trees. This practice reflects a deep respect for the environment and an understanding of the need to preserve natural resources vital to their craft.

After harvesting, the fronds are stripped into long, thin strips and prepared for dyeing and weaving. This preparation determines the quality and durability of the finished basket. The strips are carefully pulled and split to achieve consistent widths and thicknesses, a process requiring considerable skill and experience. After being stripped, the fronds are often dried in the sun before being dyed. The dyeing process is a complex art involving natural pigments derived from local plants.

Once the desired colors are achieved, the dyed strips are hung to dry and are then ready to be woven into intricate patterns. The entire process, from harvesting to final weaving, exemplifies the patience, skill, and deep connection to the natural world characteristic of Zulu basketry. Using the locally sourced, sustainable ilala palm is a key element that gives these baskets their unique character and cultural authenticity.

The Natural Waxy Coating and its Watertight Properties

A key characteristic of the ilala palm frond that makes it ideal for weaving watertight baskets is its natural waxy coating. This property is crucial to the functionality of the ukhamba, allowing it to hold liquids without leaking. When the tightly coiled and stitched basket is filled with beer or water, the moisture causes the waxy fibers to swell, which effectively seals the tiny gaps between the strands, rendering the vessel watertight.

This natural sealing process is a remarkable example of the Zulu artisans’ ingenuity. They have long understood and utilized the unique properties of their local materials to create functional and durable objects. The waxy coating contributes not only to the basket’s watertightness, but also to its strength and resilience, ensuring that it can withstand the rigors of daily use.

The ukhamba’s ability to hold liquid is not just a practical feature, but also a key aspect of its cultural and ritual significance. Its role as a vessel for utshwala, the traditional sorghum beer, is central to its use in ceremonies and social gatherings. The ability to make the basket watertight using only natural materials and traditional techniques is a source of pride for the weavers and a testament to their deep knowledge of their craft.

The natural waxy coating of the ilala palm exemplifies how the Zulu people have harmoniously integrated their material culture with their natural environment. They create objects that are beautiful, functional, and reflective of their profound understanding of the world around them. This synergy between material and maker defines the art of Zulu basketry.

Social, Ritual, and Economic Significance

The palm ukhamba has long been the preferred vessel for fermenting, storing, and serving utshwala, the traditional sorghum beer, during social and ritual events. The beer is prepared and served during rituals, celebrations, weddings, funerals, and communal gatherings. The adoption of the palm ukhamba is a response to practical considerations of material availability and technical innovation, as well as a symbolic expression of resilience, communal cohesion, and continuity in the face of social and colonial changes. As colonial and market forces threatened traditional clay pot production, the refuge in palm weaving strengthened. However, it also boosted the value of artistic basketry for tourist and collector markets, encouraging continued adaptation and innovation in forms and patterns. Today’s weavers build on this legacy by creating classic izinkhamba (the plural form of ukhamba), which have simple pattern decorations for home use, as well as experimental izinkhamba, which have complex variations in shape, color, and pattern for commercial and art markets. Yet the core ritual, symbolic, and communal associations remain intact—an affirmation of Zulu cultural resilience.

Natural Dyes and Coloring Processes

The vibrant and varied colors adorning Zulu ukhamba baskets are achieved through the use of natural dyes. This practice is both an art and a science that has been passed down through generations of weavers. Artisans draw from a rich palette of indigenous KwaZulu-Natal flora, using roots, leaves, bark, and berries to create stunning hues. This deep knowledge of the local environment is a cornerstone of the craft, with each weaver possessing a unique understanding of which plants yield specific colors and how to process them. Using natural materials connects the baskets to the land and ensures that each piece is unique, with colors reflecting the seasons and environment in which it was made.

Creating these dyes is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process. The plant materials are often boiled for extended periods to extract the pigments, which are then used to soak the prepared ilala palm strips. For instance, the bark of the marula tree is boiled to produce a deep burgundy called isfizu, and a paste of wood ash and water creates a mustard yellow called icena. Other sources include riverbank tree roots for browns and blacks and the leaves of certain shrubs for pinks and lilacs.

The availability of these materials is often seasonal, meaning the baskets’ color palette can vary throughout the year. This reliance on natural, renewable resources speaks to the Zulu people’s sustainable practices and deep respect for their environment.

The Color Palette

Undyed ilala has a natural straw/cream color. Zulu ukhamba baskets are celebrated today for their earthy yet vibrant color palettes, which include rich browns, khakis, blacks, off-whites, and shades of green. These colors are traditionally produced using indigenous dye plants, soils, and specific dyeing methods.

Black (Omnyama): Traditionally, black dye was made from the leaves of the umthombothi tree (Spirostachys africana), which is known for its dark, resinous sap. The leaves are boiled for several hours to extract the pigment, which is then used to dye the palm fronds. This process takes several days and requires great skill and patience to achieve a deep, consistent black color. Recently, weavers have started using rusted tin cans as a source of black dye. The cans are boiled with the fronds, and the iron oxide reacts with the fronds’ tannins to create a black color.

Deep brown (Ububende): Palm leaves are kept in muddy soil for up to a week to achieve this color.

Dark brown to black (Isizimane): This color is often achieved by steeping strips in iron-rich river mud or a dark dye bath. Then, the strips are boiled in water with bark from the umbulunge tree to fix the color (a natural mordanting process). Some makers also use charcoal or soot baths and repeat boils to achieve a deeper color.

Browns/reds: produced by boiling palm strips with tannin‑rich barks/roots. Exact plants vary by region and family; commonly cited in KwaZulu‑Natal are local bush gwarri or gurry (Euclea divinorum, Euclea natalensis) and acacia/vaakhaak species for warm reddish browns.

Khaki green/Khaki Brown (Mxuba): Leaves are soaked and boiled in mixtures of cow dung for several hours.

Mauve/Lilac (Ubukhwebazane): This color is obtained from indigo fern leaves. The color varies depending on how long the ilala is soaked and boiled. According to Jannie van Heerden in Zulu Basketry (Print Matters, South Africa, 2009), boiling 3 kg of indigo fern leaves in 25 liters of water for 3 to 5 hours yields delicate lilac hues.

Pink: Obtained by chopping and boiling the bark of the wild plum tree in water.

Orange (Xomisane): Obtained from the roots of the isiqomiswano plant.

Ochre: Obtained from the bluebush fruits.

Mustard/Yellow (Icena): Paste of wood ash and water. Soak overnight, then boil for 5-7 hours.

Pale Red (Bomvu): Boil palm leaves for two days with crushed leaves from a tall shrub and water.

Olive/Grey (Ijuba): achieved through lighter mud baths or shorter dye times.

These ancient dyeing practices create stunning visual diversity and root the basket in the local ecology. Each color echoes the land and the plants used. Often, specific rituals, knowledge transmission, and kinship links are involved.

Historically, the color palette of vases intended for domestic use or the local tourist market was limited. However, opening up to the international collectors’ market during the 20th century resulted in an explosion of colors and more intense contrasts. This difference is clearly noticeable when comparing old and vintage baskets with modern ones. Furthermore, beginning in the mid-to-late 20th century, some weavers started using aniline/commercial dyes to produce brighter reds, blues, and greens.

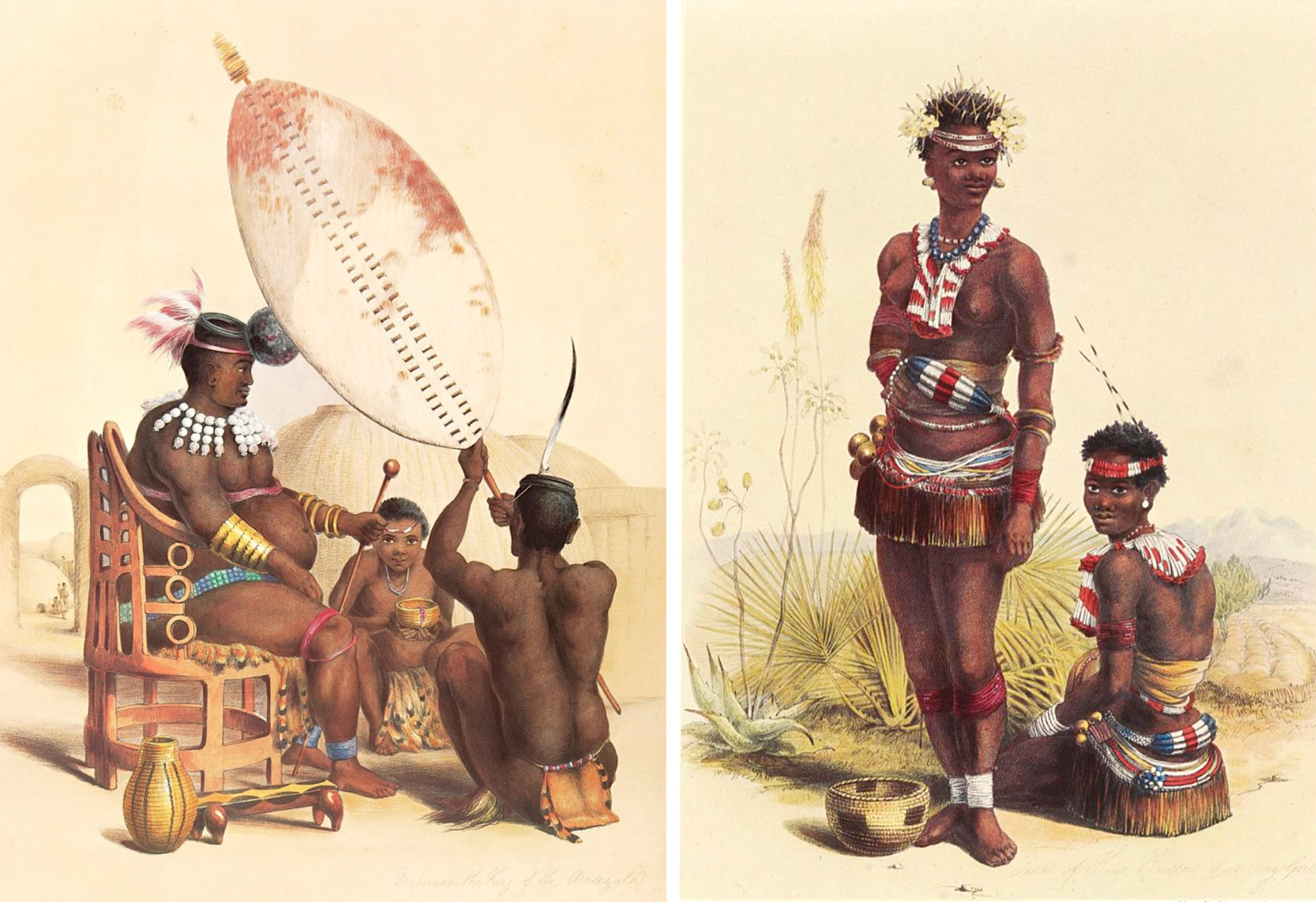

These are two hand-colored lithographs by George French Angas. They were originally printed in The Kafirs Illustrated, which was published in London in 1849. Digital Archive of the National Library of Australia.

Left: Mpande, the Zulu king, surrounded by his warriors.

Right: Two of King Mpande’s dancing girls.

Each lithograph features a basket in the bottom left corner. As you can see, the geometric patterns and color combinations are quite simple. However, these patterns and colors were not merely decorative; they held cultural significance.

Two old izinkhamba (plural form of ukhamba). Old pieces are usually covered with a dark patina.

LEFT: Antique Zulu Ukhamba, South Africa. Dimensions: 6.5 x 9 in., 16.51 x 22.86 cm. Stream City Collectibles, Olympia, WA, USA.

RIGHT: Antique Zulu Ukhamba, South Africa. Date: from the late 19th/early 20th century. Dimensions: 6 x 6 in., 15.24 x 15.24 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by John Moran Auctioneers, Monrovia, CA, USA.

Two vintage izinkhamba.

LEFT: Vintage Zulu Ukhamba Lidded Basket, South Africa, eBay, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

RIGHT: Vintage Zulu Ukhamba Lidded Basket, South Africa. Height 11.5 in., 29.21 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Ethnika Home Decor & Antiques, New Rochelle, NY, USA.

Collector-quality modern ukhamba, Kwa-Zulu, South Africa. Dimensions: height 10 in., 25.4 cm; diameter 9.5 in., 24.13 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Ace Of Estates, Carefree, AZ, USA.

Large modern Zulu ukhamba, South Africa. Dimensions: height 19.68 in., 50 cm; diameter 17.71 in., 45 cm. Zohi Interiors, Kansas, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. African traditional ukhamba. Dimensions: 18 x 14 x 14 in.; 45.72 x 35.56 x 35.56 cm. Auctioned in 2025 by Hill Auction Gallery Sunrise, FL, USA.

2. Vintage ukhamba. Dimensions: 19 x 32 in., 48.26 x 81.28 cm. Found Rental Co., CA/AZ, USA.

3. Vintage ukhamba. Dimensions: 11 x 20 in., 27.94 x 50.8 cm. Found Rental Co., CA/AZ, USA.

4. Contemporary ukhamba made of ilala palm and ncebe (wild banana) by Phuzile Sibiya. Height: 25 in., 63.5 cm. Auctioned in 2020 by Leland Little, Hillsborough, NC, USA.

Modern izinkhamba.

Sources: 1. Pinterest; 2. Bambizulu; 3. Pinterest; 4. African Design.

Construction Techniques

Ukhamba baskets are generally coiled with an exceptionally tight and even weave, rendering the vessel nearly watertight. Weavers use fine weaving spears to manipulate each stitch, often over the course of several weeks. This technique reflects a combination of familial (often matrilineal) instruction and individual creative expression.

LEFT: Illustration by Silvia Koros from Northwest Coast Basketry, Burke Museum, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

CENTER TOP: Obakki Journal.

Design, Patterns, and their Meaning

The patterns woven into Zulu izinkhamba baskets are not merely decorative. They are a form of visual language that carries deep cultural significance and conveys specific messages. Geometric patterns are a common feature of Zulu basketry, and each shape and motif has its own symbolic meaning. These patterns allow the weaver to express her identity, social status, and the purpose of the basket. Using these traditional patterns preserves and transmits cultural knowledge from one generation to the next, ensuring the continuity of Zulu heritage.

Common geometric patterns on izinkhamba include triangles, diamonds, and zigzags, each with a specific meaning. These patterns are often combined in complex ways to create intricate designs that tell stories or convey messages. The choice of patterns is not arbitrary. It is a deliberate and thoughtful process reflecting the weaver’s understanding of her culture and her place within it.

The patterns are a source of pride for the weaver and her community and celebrate the Zulu people’s rich artistic traditions.

Patterns are created by placing dyed and undyed stitches in specific sequences on the coiled form. Because the basket is round and swells and contracts, zigzags, chevrons, diamonds, lozenges, bands, and spirals dominate—forms that read cleanly on curvature and remain watertight.

About “meanings” – an important caveat

In academic and museum field notes, pattern names are often descriptive rather than fixed symbolic codes. A single motif may have different nicknames or associations within different families or regions. Some “meanings” promoted in galleries (e.g., “this diamond means fertility everywhere”) are market simplifications.

What remains consistent is that motifs frequently reference the landscape, livestock, and homestead architecture, such as fences, gates, and kraals. They also reference the flow of beer and celebration—things central to Zulu rural life.

Makers also use patterning to demonstrate their skill, balance, and memory (a family’s “hand”). In some households, a recurring motif functions as a signature.

Now, we will see some recurring symbols, but always bear in mind that assigning a rigid meaning inevitably involves a certain degree of simplification.

Triangles: Masculinity and Married Men

The triangle is a fundamental geometric pattern in Zulu basketry and is widely recognized as a symbol of masculinity. This association is deeply rooted in Zulu culture and reflected in various art forms. The meaning of the triangle becomes more nuanced when it is used in combination with other shapes. For instance, a double triangle with its points facing inward to form an hourglass shape symbolizes a married man. This design signifies the union of two individuals and the formation of a new family. Using the triangle to represent both individual men and the institution of marriage highlights these concepts’ importance in Zulu society. The triangle is a powerful, versatile symbol used to convey meanings related to male identity and social roles.

Four izinkhamba displaying the triangular geometric pattern.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Ukhamba basket. Dimensions: Dimensions: width 13 in., 33 cm; height 14 in., 35.56 cm. Auctioned in 2018 in Cincinnati, OH, USA.

2. Ukhamba basket woven by Trifina Gamedi. Height: 17 in., 43.18 cm. Baskets of Africa, Los Ranchos, NM, USA.

3. Zulu Wedding Basket. Auctioned in 2016 by 21st Century Auctions, Saugus, CA, USA.

4. Ukhamba basket by Bongeliwe Dlamini. Height: 8 in., 63.5 cm. Baskets of Africa, Los Ranchos, NM, USA.

Diamonds: Femininity and Married Women

Unlike the triangle, the diamond is the primary symbol of femininity in Zulu basketry. It is often associated with the female form and fertility, both of which are central to women’s roles in Zulu society. Similar to the triangle, the meaning of the diamond expands when it is used in a double form. A double diamond symbolizes a married woman, representing her union with her husband and her roles as a wife and mother. This design is often used on baskets given as wedding gifts or used in marriage ceremonies. There, it serves as a blessing for the new couple and a symbol of their future together.

Zig-Zags: The Spear of Shaka

The zigzag pattern is another common Zulu basketry motif and a direct reference to the spear of Shaka Zulu, the legendary founder of the Zulu nation. A towering figure in Zulu history, Shaka’s military innovations—including the introduction of the short stabbing spear (iklwa)—transformed the Zulu kingdom into a formidable power. The zigzag pattern is a stylized depiction of this iconic weapon. Its use in basketry honors Shaka’s legacy and celebrates the Zulu people’s military prowess. This dynamic and energetic design adds a sense of movement and power to the basket. It is often combined with other patterns, such as triangles and diamonds, to create complex, visually striking designs. It is often used as a symbol of strength, courage, and the enduring spirit of the Zulu nation.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Ukhamba Basket made of ilala palm fibers colored with natural dyes. Height: 15.5 in., 39.37 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by Jasper 52, New York, NY,

USA.

2. Ukhamba Basket with zig zag pattern. Dimensions: height 14 in., 35.56 cm; diameter 16 in., 40.64 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by The Benefit Shop Foundation Inc., Mount Kisco, NY, USA.

3. Vintage, giant Ukhamba. Dimensions: 12.25 x 39 in.; 31.12 x 99.06 cm. Found Rental Co., CA/AZ, USA.

4. Ukhamaba basket with zig zag pattern on the body and lid. Dimensions: 15 x 23 x 15 in.; 38.1 x 58.42 x 38.1 cm. Auctioned in 2020 in Atlanta, GA, USA.

Modern izinkhamba with zig-zag patterns. Source: Pinterest.

Series of Diamonds: The Shields of Shaka

The shield is another important symbol of Zulu military tradition, in addition to the spear. It is also represented in Zulu basketry patterns. A series of interconnected diamonds is said to represent the shields of Shaka’s warriors. The Zulu shield, called isihlangu, was large and oval-shaped, made from cowhide. It was an essential piece of equipment for every Zulu soldier. It was used not only for protection in battle, but also as a symbol of the warrior’s identity and loyalty to his regiment and king. The pattern of interconnected diamonds is a powerful, evocative design that speaks to the unity and strength of the Zulu nation. It reminds us of the importance of community and the collective spirit that has enabled the Zulu people to overcome many challenges throughout their history. Using this pattern on an ukhamba, a vessel used to bring people together in a spirit of sharing and fellowship, is particularly appropriate. It symbolizes the bonds that unite the Zulu people and their shared heritage.

BELOW

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Portrait of Uyedwana, a Zulu in visiting dress. He is wearing a wool and feather kilt, a headdress with colored plumes, and streamers of wool on his arms and legs. He is holding assegais and a white shield in his left hand and a knobbed stick in his right. Behind him is a calabash on the left. Watercolor by George French Angas, ca. 1847. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

2. Zulu dancing shield made of red and white oxhide with black “stitches” and fur pompom, ca. 1909. . © The Trustees of the British Museum. London, UK.

3. Zulu stabbing spear with an iron blade and wooden shaft, KwaZulu-Natal, ca. 1879. © The Trustees of the British Museum. London, UK.

4. Utimuni, Zulu warrior, nephew of the Zulu king Chaka. Lithograph by George French Angas, printed in London in 1849. Digital Archive of the National Library of Australia.

LEFT: Portrait of Umzingulu, a Zulu chief, with a soldier. A Zulu captain, or induna, is seen in the foreground. Nearly naked, he wears a feathered headdress and beaded and woolen ornaments. He stands grasping a shield and assegais in his left hand. Behind him, at L, is the back view of a Zulu soldier turned to the right. Watercolor by George French Angas, ca. 1847. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

CENTER: Zulu warrior with a decorated shield and spear. He wears headgear with feathers, an ear ornament, and a necklace. He is also wearing feather ornaments around his neck, waist, and legs. Watercolor on paper by Nguni, 19th century. © The Trustees of the British Museum. London, UK.

RIGHT: Zulu warrior in full regimental regalia, carrying the large isihlangu war shield, ca. 1860. His upper body is covered in cow tails; his kilt is made of spotted cat, civet, or genetskin; and his shins are decorated with cow tails. The elaborate headdress consists of a brow band and face-framing flaps of leopard skin, with an additional band of otter skin above. There are multiple ostrich feather plumes and a single upright crane feather.

Four izinkhamba showing the female design of a series of diamonds and the “shield of Shaka” pattern. The second basket from the left was made by artist Tombi Zulu. It’s 18 in. – 45.72 cm tall, and was auctioned in 2022 by Bradford’s Auction Gallery, Sun City AZ, USA. The basket on the right is an ukhamba 20 in., 50.8 cm tall. It was auctioned in 2018 by Clars Auctions, Oakland, CA, USA.

Patterns Representing Life Events and Aspirations

Beyond the basic symbols of masculinity and femininity, Zulu ukhamba basket patterns represent a variety of life events, aspirations, and blessings. They are a way for the weaver to express her hopes and dreams for the future and celebrate life’s joys and milestones. Using these patterns infuses the basket with positive energy and good wishes, making it a powerful, meaningful gift or sacred object for ceremonies. Patterns representing life events and aspirations tend to be more complex and abstract than basic geometric shapes and can be interpreted in various ways, depending on the context. They are a testament to the creativity and imagination of Zulu weavers who have developed a rich, nuanced visual language to express the full range of human experience. Using these patterns celebrates life in all its complexity and reminds us of the Zulu people’s deep spiritual and emotional connection to their craft.

Checkerboards, Whirls, and Circles: Good News, New Birth, and Good Rains

These patterns are often used on ukhambas to represent good news, new birth, and good rains. The checkerboard pattern, with its alternating light and dark squares, symbolizes balance and harmony. It is often used to celebrate a new beginning or positive change in fortune. The whirl pattern, with its spiraling lines, symbolizes the cyclical nature of life and the continuous flow of energy. It is often used to represent the birth of a child or the start of a new project. The circle, with its unbroken line, symbolizes eternity and the interconnectedness of all things. It often represents hope for a long and prosperous life. Using these patterns infuses the basket with positive energy and good wishes. A weaver may incorporate these patterns into a gift basket or use them to decorate a basket for a special occasion ceremony.

Beer baskets are tied to communal beer brewing and sharing, such as at weddings, ancestor rites, and harvests. Patterning that encircles the vessel mirrors circulation and social cohesion. Many scholars point out that form, function, and surface all reinforce containment, temperance, and reciprocity.

Very fine and large Ceremonial Ukhamba, second half of the 20th century, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Dimensions: height 28 in., 71.12 cm. Cultures International From Africa, CA, USA.

The Ukhamba Wedding Basket

A special type of ukhamba, wedding baskets are used in marriage ceremonies and given as gifts to the newlyweds. Often, these baskets are decorated with a combination of diamonds and triangles, which symbolize the union of a man and a woman. This combination is a powerful symbol of joining two lives and creating a new family.

Wedding baskets often have more intricate and elaborate patterns than other types of ukhambas, reflecting the importance of the occasion. A weaver may spend weeks or months creating a wedding basket and often incorporates personal touches and creative flourishes into the design. The resulting basket is a beautiful, functional object and a powerful symbol of love, commitment, and hope for a long, happy life together. Wedding baskets are a testament to the deep cultural significance of marriage in Zulu society and remind us of the important role the ukhamba plays in celebrating life’s most significant milestones.

In the Zulu tradition of lobola, or bride-price, the ukhamba plays a relevant role. This practice involves the exchange of cattle or other goods between the families of the bride and groom. During lobola negotiations, the ukhamba is often used to serve beer, symbolizing the hospitality and goodwill of the host family.

The ukhamba also symbolizes the bride’s value and importance. Its intricate patterns and fine craftsmanship reflect the bride’s worth and her family’s status.

Wedding Ceremony Among the Zulus or Zulu People of Southern or South Africa. Engraving by Castelli, 1879. Private Collection.

A traditional Zulu wedding in the 1930s.

How can you recognize a wedding ukhamba basket?

- Meaningful Geometry:

- Diamonds: Traditionally associated with femininity and fertility, echoing the basket’s role in marital rites.

- Triangles: Signify masculine energy, often connected to the husband or ancestral lineage.

- Zigzags and hourglasses: Hourglass motifs may denote marital status (e.g., married men or women), while zigzag patterns reference strength, protection, and lineage. Historically, zigzags referenced the “Assegais of Shaka,” which symbolized martial prowess and ancestral male strength. Other diamond variations represented the “Shields of Shaka” and feminine protection.

- Combined Motifs: Wedding baskets often integrate multiple geometric forms, representing the union of two lineages and the coming together of families. There is a deliberate layering of meaning—each motif is chosen for its social and ancestral significance.

- Natural Hues: The palette is defined by the use of exclusively natural dyes: browns from mud-soaked palm leaves, deep blacks from bark and mud mixtures, khakis from cow dung baths, and rare lilacs or reds from special shrubs. This color tradition is crucial for wedding baskets, because it signals a connection to the local ecology and ancestral knowledge.

- Symbolic Color Use: Certain colors, such as rich browns, deep blacks, and subtle reddish hues, are favored for wedding baskets. These colors signify abundance, purity, and fertility for the new couple.

- Ritual Dyeing: The process of creating wedding baskets involves ritualistic acts and is sometimes accompanied by songs, stories, or blessings from older women, which further embeds the act in the symbolic landscape of the wedding.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Large museum-quality Marriage Basket, Pinterest.

2. Large museum-quality Marriage Basket. Height: 31 in., 78.74 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Greenwich Auction, Stamford, CT, USA.

3. Large Marriage Basket. Height: 31 in., 78.74 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Greenwich Auction, Stamford, CT,

4. Ovoid Wedding Ukhamba. Height: 30.5 in., 77.47 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by Freeman’s | Hindman, Chicago, IL, USA.

Teardrop-shaped Wedding Ukhamba by Kowlina Gwenba. Height: 19.5 in., 49.53 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Thomaston Place Auction Galleries Thomaston, ME, USA.

The Weaver’s Personal Narrative in the Patterns

The patterns on a Zulu ukhamba are not just a collection of abstract symbols. They reflect the weaver’s personal identity and ancestral lineage. A weaver may incorporate patterns associated with her clan or family or use patterns with personal significance. The basket becomes a means for the weaver to recount her story, express her unique perspective on the world, and connect with generations of women before her.

Using patterns to express identity and ancestry is a powerful tradition in Zulu culture. A weaver is not merely creating a functional object; she is creating a work of art that reflects who she is and where she comes from. Baskets preserve and transmit cultural knowledge from one generation to the next and are a testament to the Zulu people’s deep connection to their heritage.

The patterns on the ukhamba remind us that every object has a story to tell and that each story contributes to a larger collective narrative.

Zulu ukhamba patterns can also be used to tell stories, convey proverbs, and share other forms of traditional wisdom. A weaver may incorporate motifs associated with a legend or myth or use patterns that visually represent a proverb. The basket becomes a canvas for storytelling, sharing the Zulu people’s rich oral traditions with a wider audience.

Using storytelling in basketry is a testament to the Zulu weavers’ creativity and imagination. They have developed a rich, nuanced visual language capable of conveying complex ideas and emotions. The ukhamba is not just a container for beer; it is a vessel for knowledge, wisdom, and cultural heritage. The patterns on the ukhamba remind us of the power of art to communicate across cultures and connect us with the stories and traditions of our ancestors.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Very fine ukhamba basket made before 1990. Height: 15 in., 38 cm. Sold in New Mexico, USA, via eBay.

2. Museum-quality tall ukhamba basket. Dimensions: height 20.5 in., 52.07 cm; diameter 16 in., 40.64 cm. Worldesigns, NY, USA.

3. Museum-quality tall ukhamba. Dimensions: height 17 in., 43.18 cm; diameter 16 in., 40.64 cm. Worldesigns, NY, USA.

The variety of shapes and sizes of izinkhamba

The traditional ukhamba basket is easily recognizable by its rounded, bulbous body that tapers into a narrow neck. This shape is inspired by its ancestor, the clay ukhamba pot. This silhouette is designed for functionality (holding and pouring beer) and symbolism (communal unity, abundance, hospitality, and fertility). The curvature of the basket allows it to stand stably and be easily stored, and the neck helps retain the contents and is suited to communal drinking customs.

While the classic ukhamba shape remains popular, there are regional and artistic variations in Zulu basketry.

- Neck shape: Some baskets have elongated necks, while others are nearly spherical with only a slight opening.

- Shoulder and base: The curves at the shoulder (the transition from the body to the neck) may be sharp or gentle, and the bases may be broader or more rounded, depending on the local style or the intended use.

- Decorative forms: Highly skilled weavers sometimes experiment with exaggerated curves or subtle flaring to showcase their artistry or to fulfill specific ritual functions.

Ukhamba baskets are woven in a wide variety of sizes, from modest daily vessels to enormous ceremonial icons, to serve different purposes and occasions in Zulu society. Each size and shape variation responds to practical needs and carries deep symbolic and communal significance, reflecting the adaptive artistry of Zulu master weavers.

- Small Ukhamba (15–25 cm high): Used for the everyday serving of utshwala (sorghum beer) at home. Also made as gifts or decorative objects.

- Medium-Sized Ukhamba (30–40 cm high): Ideal for extended family or small communal gatherings.

- Large Ukhamba (50–70 cm high): Designed for major celebrations or rituals, it holds beer for large groups, such as at weddings or funerals.

- Giant Ukhamba (up to 1 m and above): These extraordinary baskets are woven for major feasts, clan gatherings, or symbolic and artistic displays. “Giant” Ukhamba baskets are rare, requiring exceptional skill and extended labor. They often take pride of place in ceremonial contexts or collections. Their size emphasizes themes of generosity, prestige, and abundance.

The size of an ukhamba is closely linked to its social significance. Larger baskets often signify prestige and play an important role in ceremonies marking significant life events, such as weddings. They also demonstrate weaving prowess—only the most skilled artisans attempt to weave giant ukhamba baskets. These pieces are prized both locally and among collectors and museums for their complexity and visual impact.

Now, take a close look at the ukhamba below.

Zulu Ukhamba. Dimensions: height 38 in., 96.52 cm; diameter 24.5 in., 62.23 cm. Sold by Africa and Beyoond Art Gallery, San Diego, CA, USA.

This ukhamba basket is just under a meter high. However, the first photo does not do justice to its enormous size. The photo below does, and it will leave you speechless.

Photo Courtesy: Africa and Beyoond Art Gallery.

Surprised, right? Below are some examples from different sources showing just how big some Zulu baskets can be. Ukhamba baskets and open baskets can reach considerable sizes and have a remarkable sculptural presence. If you want to buy a Zulu basket online, be sure to check its dimensions first!

The male and female Zulu weavers proudly present their masterpieces.

Sources.

Above: © Peter Magubane, South Africa Online; Pinterest; The Silk Road Fair Trade Market; IThunga Africa; Basket of Africa, Bino & Fino.

Below: Vukani Museum, Bambizulu, IThunga Africa, Pinterest.

The ukhamba below is a giant basket, masterfully handwoven by Agnes Mlotshwa, who comes from a family of weavers renowned for making extremely fine lidded baskets. This amazing piece is an all-natural, traditional basket — no synthetic dyes were used — woven by wrapping strips of naturally waxy ilala palm fronds around coils of wild grasses. It’s a truly impressive specimen, measuring 42.25 inches (107.315 cm) in height (not including the stand).

Giant, modern Ukhamba basket handwoven by Agnes Mlotshwa. Height: 42.25 in., 107.315 cm (without the stand). Baskets of Africa, Los Ranchos, NM, USA.

Below is a ceremonial ukhamba. Though not as imposing as the one above, this ukhamba is still a giant, standing 32 inches (81.28 cm) tall with a circumference of 74 inches (188 cm). It also displays extremely fine workmanship.

Large ceremonial Ukhamba basket handwoven from the Ilala palm and grass. Dimensions: height 32 in., 81.28 cm; circumference 74 in., 188 cm. Cultures International From Africa To Your Home, CA, USA.

Giant baskets in the Vukani Craft Museum, housed within the grounds of Fort Nongqayi at Eshowe (South Africa), an authentic piece of Zululand history. The Vukani Craft Museum boasts the largest and most valuable collection of Zulu crafts in the world. The basket on the right was handwoven by Angeline Bonisiwe Masuku.

The Ukhamba as a Contemporary Art Form: Innovation in Design and Materials

In recent years, the ukhamba has evolved from a traditional, functional object into a celebrated art form. Master weavers are constantly pushing the boundaries of the craft by experimenting with new designs, patterns, and materials. They create stunning works of art that are sought after by collectors and museums worldwide.

This innovation is a testament to the Zulu people’s creativity and adaptability. They are transforming a traditional craft into a vibrant, dynamic art form that remains rooted in the past while responding to the present. The contemporary ukhamba symbolizes the Zulu people’s deep connection to their heritage and their capacity to find beauty and meaning in an ever-changing world.

Angeline Bonisiwe Masuku

Born in 1967 in Hlabisa, KwaZulu-Natal, Angeline Bonisiwe Masuku is an award-winning master weaver. She is recognized both nationally and internationally for her exceptional ilala palm basketry, as well as for her dedication to Zulu traditions, women’s empowerment, and artistic innovation.

She began learning to weave at the age of eight (in 1975) from her aunt, the master weaver Kwawulina Gwcensa. Masuku works almost exclusively with ilala palm, which she harvests, prepares, and dyes using local, natural plant sources, such as isizimane root for black or dark brown and umdoni for purple. She believes that using traditional processes is paramount, and she insists on using indigenous techniques, making each piece a document of Zulu heritage.

Her baskets feature traditional Zulu geometric patterns with symbolic meanings. She draws inspiration from beadwork and elements of the rural environment, merging traditional motifs with innovative abstractions informed by contemporary contexts.

Masuku considers herself both a craftswoman and an artist. While distinguishing between “method” in traditional craft and contemporary art, she maintains that traditional knowledge is foundational for innovation. Rather than planning designs in advance, she allows patterns to “come out of her head and through her hands into the basket,” resulting in dynamic and often playful arrangements. In interviews, Masuku has emphasized the interconnectedness of basketry, architecture, and memory. She often incorporates shapes and motifs reminiscent of the rondavel huts of her rural upbringing. She once said, “Living in a rural area, traditional crafts are important because they remind us where we come from and who we are.”

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

Angeline with a tall basket, photo Selvedge Magazine.

Ukhamba Basket, 2023 by Kznsa Online Gallery, Durban KwaZulu-Natal.

Photo Vuk’uzenzele Newspaper.

Large Ukhamba Basket, 2023 by Kznsa Online.

Hlabisa Basket by Kznsa Online.

Baskets by Angeline, Selvedge Magazine.

A tall ilala palm and ukhasi grass fibre basket, height 37.40 in., 95 cm, Strauss & Co., Johannesburg/Cape Town, South Africa.

Reuben Ndwandwe

Reuben Ndwandwe (1943–2007) was one of South Africa’s most distinguished nd award-winning Zulu master weavers. His technically and aesthetically exceptional baskets have been collected by major institutions and celebrated locally and internationally.

Born in Hlabisa in northern KwaZulu-Natal, Ndwandwe learned basket weaving from his mother and grandmother, who were experienced traditional crafters. His early mastery of ancestral techniques formed the basis for his innovative career.

He primarily used ilala palm and employed traditional coiling and stitching techniques. However, he was renowned for introducing new motifs, unusually fine overstitching, and pattern densities that gave his baskets a lacelike texture and remarkable structural coherence.

His baskets, particularly the imbhenge and unyazi types, were celebrated for their diamond and zigzag patterns that integrated heritage symbolism with contemporary artistic expression. While his work was rooted in Zulu aesthetics, Ndwandwe was innovative, often combining bold geometry with subtle chromatic effects derived from natural dyes.

His work is described as blurring the line between utilitarian craft and fine art. His baskets showcase a mastery of technical control, material refinement, and complex visual logic. He is often credited, alongside master basket makers such as Beauty Ngxongo and Nesta Nala, with setting new standards for excellence and creativity in Zulu basketry.

His combination of technical rigor, artistic innovation, and commitment to cultural transmission made him a seminal figure in the modern resurgence of Zulu basketry. As one of the few men to carry on the weaving tradition, which was historically passed down to women, he played a leading role in production and teaching. He was integral to the Vukani Association, a key organization in the revitalization of Zulu crafts since the 1970s. Through Vukani, he promoted knowledge sharing, product refinement, and community economic development.

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

Reuben Ndwandwe with one of his creations.

Lidded basket from the 1990s. Dimensions: height 9 in., width 10 3/4 in. – 22.9 × 27.3 cm. The MET, New York, NY, USA.

Basket. Photograph: Anthea Martin.

Ukhamba basket with lid, 1990; height 24 cm, diameter 23 cm, Strauss & Co., Johannesburg/Cape Town, South Africa.

Zulu basket with lid, early 21st century, height 27 cm, diameter 28 cm, Strauss & Co., Johannesburg/Cape Town, South Africa.

Ukhamba basket with lid, private collection.

Reuben Ndwandwe with one of his creations.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?